STARFIELD AND HOW TO FIND MEANING IN INFINITE FAKE WORLDS

[OPEN SPOILERS AHEAD!]

of all the big-budget triple-A games of 2023, i assure you, this is the last one i thought i'd end up writing about. it's Skyrim in space. how much could i have really found to say?

for decades now, Bethesda Games Studios' titles have held a pretty unique spot in the medium. i still remember trying Skyrim for the first time on New Year's Eve - probably having watched my parents play Oblivion when i was younger and being curious about what's up with these dang old-ass scrolls? - and taking some absurd hike through the mountains to get to Solitude against all better judgment. with hindsight, i kind of chalk it up to being a bit more naive and impressionable about what Real Gamers thought was cool, but it's hard to argue that for a hot minute there, Bethesda was THE studio leading western-style RPGs into a 21st century open-world renaissance. i have plenty of gripes with their general formula and approach to game design that you'll become intimately familiar with by reading this piece, but i think it's important to lay the groundwork that their prestigious reputation didn't come out of thin air. no other studio was (or still is) devoted to the types of things Bethesda really cares about doing, and when Skyrim took off and became a massive multi-demographic hit, it left its fingerprint on entire genres of video games for the following decade.

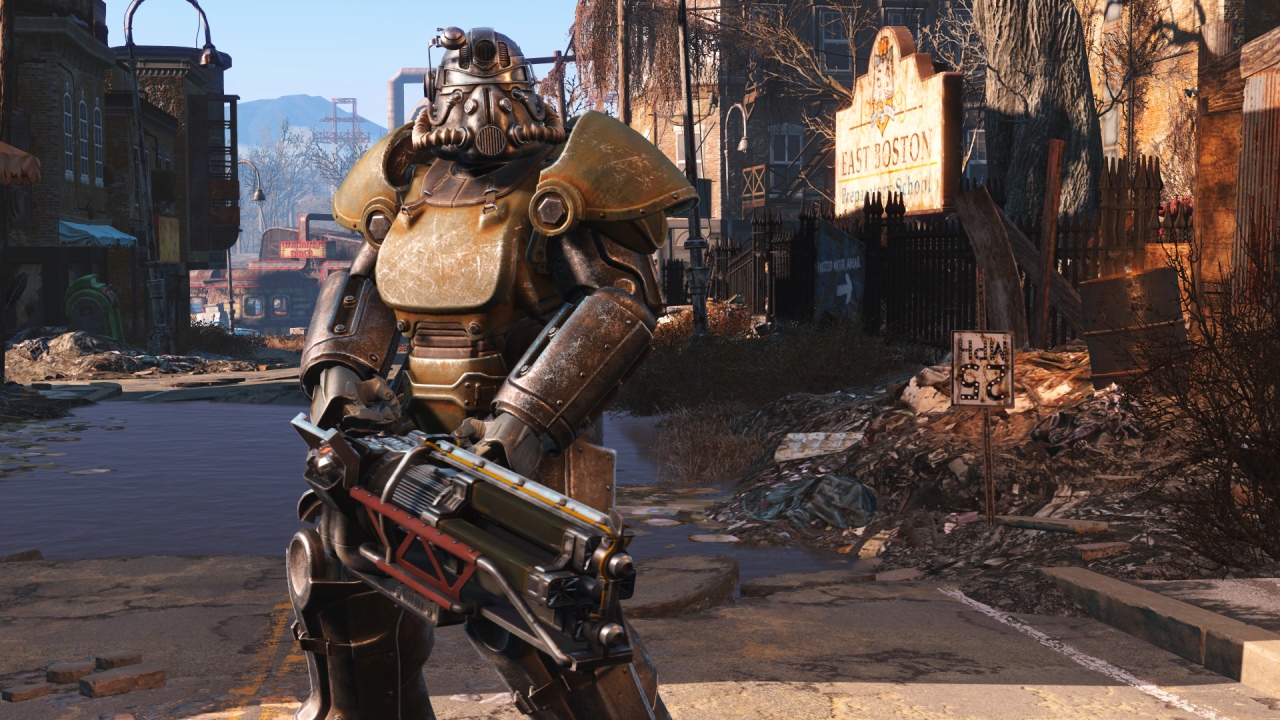

then, of course, there's Fallout, Bethesda's inherited second franchise, skewing for a much more distinct blend of post-apocalyptic Americana tinted by sci-fi pulp. The Elder Scrolls might be the first of Bethesda's franchises that i really properly fooled around in, but over time, Fallout is the one that's won my heart, with its kitshcy aesthetic and approach to how old habits, be they personal or societal, endure and mutate through armageddon.

and for a long time, that was it! Bethesda as a publishing entity has plenty of games they've overseen, but their in-house work has always bounced back-and-forth between these two titans of the genre, and one of them was acquired from another studio entirely, transformed from an isometric PC game into a more palatable, more Bethesda-y first-person affair. it's only now, almost thirty years after The Elder Scrolls: Arena, and in the midst of an unprecedented corporate acquistion by Microsoft, that we're finally ready to see a new world crafted by one of the most storied and prolific studios in RPG history. you've heard of Fantasy Game, you've heard of Apocalypse Game, but finally, Todd Howard has delivered us the third possible game from the periodic table of games - Space Game.

i had, honestly, relatively low expectations for Starfield. it was shrouded for secrecy in so long - seriously, i'm only barely joking when i say it really was pitched as just "Bethesda's doing a Space Game" - and when it finally came time to actually see it, the first impressions ended up feeling kind of low-impact, whether it was Todd Howard saying the quiet part loud and calling it "Skyrim in space" or Phil Spencer pre-emptively lowering the bar in an effort to make a broader point about how the Xbox division has found itself backed into a real tough corner. it wasn't entirely Bethesda's fault, though. what really sealed the deal for me were their friends/rivals/new neighbors over at Obsidian Entertainment.

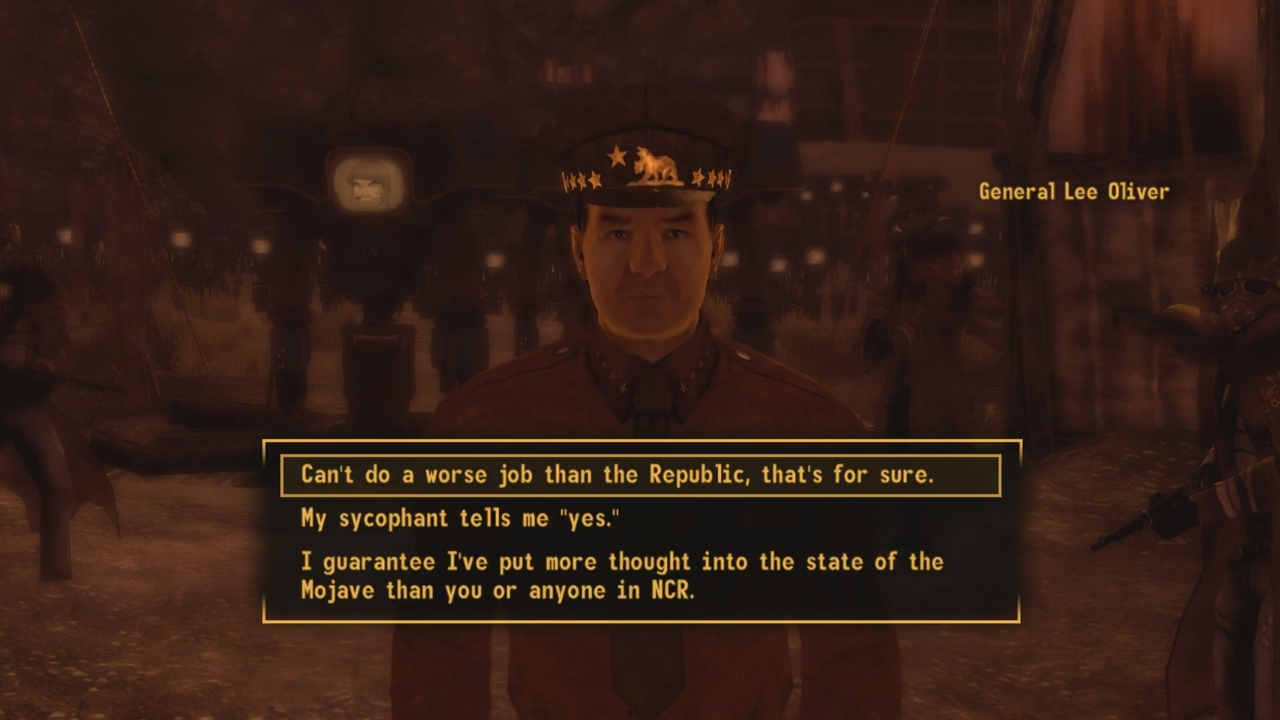

i don't really know how much of an introduction i need to provide for Fallout: New Vegas, because for the longest time, all i knew was it was the one people really liked, the one people made hours-long video essays about, the little RPG that could with a cult following dying to let you know how well it still held up. in case you're unfamiliar, New Vegas is a spinoff of the franchise, developed in the Fallout 3 engine to hold fans over while Bethesda focused on Skyrim. it was made by a studio full of people who had worked on the original top-down Fallout games, and sort of splits the difference on two very different styles, combining the gameplay skeleton of a late-2000s Bethesda game with the deeper character-building and west coast setting of the Interplay titles. upon release in 2010, New Vegas did alright for itself, but was famously a little rough around the edges, ultimately losing out on bonus pay for Obsidian over a handful of points on Metacritic and culturally seeming largely overshadowed by Skyrim the next year.

i had tried New Vegas's opening sequence on consoles a few times over the year, but always bounced off it a little bit. come January 2023, though, and i was longing for a game i could really sink my teeth into while i stayed cozy over the winter. finally armed with a certified Computer For Gamers, i decided to install it and give it a shot, and i went absolutely head-over-heels for it. it is, as i write this, one of my absolute favorite games i've ever played, and the only thing stopping me from writing about it on HYPERFIXT was a sense that i was late to the party, that people have spent years making compelling arguments for its status as perhaps the best RPG of all time and that i'm the silly one here for not listening sooner.

the real story here isn't the immaculately crafted narrative of ideological tensions coming to a head in the post-post-apocalyptic Mojave wasteland, though. no, the real story is a tragedy, because nobody else does it like Obsidian did, even Obsidian themselves. i've had fun fooling around in Skyrim here and there, sure, but i've never actually sat down and finished a playthrough of it, for reasons spanning from 'too big, got distracted' to 'i literally don't care about my mystical destiny'. when the pendulum swung the other way and Bethesda made Fallout 4, they took things back to the east coast and, along the way, happened to ditch basically every facet of meaningful role-playing and choice, instead going all in on a sort of psuedo-DayZ approach to crafting and building. Obsidian's own The Outer Worlds is a fairly good time and managed to beat Starfield to the punch in some respects, but it's also decidedly scaled down and hits a little different with its blunter, wackier approach to satire.

so, after years of waiting and presumably COVID-driven delays, when it finally came time to unveil what Starfield was going to be... it really did look like just another Bethesda game. one with interesting touches, sure, but falling into all the same trappings that have lost a lot of their shine since 2011. when Todd Howard boldly proclaimed that this game was going to have hundreds of star systems with thousands of planets, that wasn't exciting to me. it made me recoil, because i knew immediately that there was no way they made all of that breadth meaningful, and because the best Bethesda-style RPG is one that they didn't even make, where another studio came in and dialed the scale way, way back to focus on a tightly constructed, deeply connected, highly interactive world.

but, then again, here we are, and i played Starfield anyways, to some form of completion. the best defense i can muster up is that Bethesda's games are like potato chips to me. no, i wouldn't run out and recommend them to a friend as the height of what the medium has to offer, and i probably won't even finish the whole bag, but they're tasty enough and easy to eat a lot of. Microsoft being caught in a race to the bottom on pricing and availability certainly plays a part here too, since it meant the only major sacrifice on my end was one of digital storage space.

i guess right off the bat, an important thing to establish is that i didn't have a bad time playing Starfield. i have lots of gripes with it, big and small, but it generally wasn't a chore to keep playing it, and i spent plenty of time actively going out of my way to find more stuff to do in it, so clearly i didn't hate it outright. there's a lack of technical polish around the edges - the game loved to hitch up and freeze entirely if i tried to open my inventory too fast after landing on a new planet, for example - but the moment-to-moment gameplay feels good. this is really BGS's first time making such a gun-heavy game without the aid of Fallout's VATS system to fall back on, and they honestly pulled it off, because combat feels good, with a variety of interesting tools worth switching between and a pretty tight flow.

if there's one system i'd actually really praise whole-heartedly, it'd be the spaceships. pretty much everything else, good or bad, feels hodgepodged together from Bethesda's history, recontextualized and given maybe a few extra passes of polishing. the spaceships are the one thing i would say Starfield can unequivocally call its own, and you can tell the developers realized how much of that sci-fi power trip hinges on the spacecraft, because they handled it all really well. flight controls don't feel like i'm wrestling against them, the little D-pad power distribution system hits a good balance between being fiddly and fun, and while it took me a while to come to grips with the game's ship-building mechanics, i actually found it to be one of my favorite aspects once i got into the groove of it. the addition of being able to disable enemy ships and seamlessly board them is also really impressive and actually feels worth doing, whether it's to deal with your enemy on more even footing or to steal a new vessel for your collection.

other than that... it's Bethesda, through-and-through. sometimes, it really does feel like they spent the last eight years between Fallout 4 and Starfield in their own little bubble, ignoring a lot of what's happened to video games as a medium since then. a lot of the little touches that have always felt a little stilted and mechanical about Bethesda's titles are still here without much to paper them over. there's not really much in the scripted quest design of this game that feels like it wouldn't have been possible a decade ago, and the procedurally generated 'radiant quests' feel just as hollow as ever, if not moreso thanks to how this game handles procedurally generating entire planets.

it should be immediately obvious to anyone who knows the first thing about video games that of course Bethesda didn't handcraft 1000 planets with unique content. you're only going to get that kind of scope if you start working algorithmically, creating distinct pieces that can be slotted together into a decent enough solution by a computer. the issue, to me, is how much of that scope is really worth it. in a game like Skyrim or Fallout, it's not that hard to smudge the line between overt design and procedural generation - drop a rusty shack in the middle of the woods, or place a bandit encampment in a cave, and just let players stumble into it naturally as something to do if they're out wandering. 'wandering', in Starfield, is fundamentally different, though. you're not walking out into the wilderness, you're making jumps between distant stars and scanning planets for their resources and outposts. Starfield is set in a world where space travel has become stagnant, boring, and taken for granted, and the harsh drop-off in quality between handcrafted settlements like Neon and procedurally generated backwater planets honestly reinforces that feeling within me as a player, because exploration doesn't end up feeling especially rewarding.

one of the many side quests i encountered in my travels was a visit to a facility called the Eleos Retreat, meant to be some kind of isolated rehabilative colony for convicts. it's still under construction, though, and one of its workers has gone missing. it's a long back-and-forth of finding a missing person and negotiating with bounty hunters who see the Retreat as easy pickings thanks to how many wanted targets are living there, but the point of me bringing this up is the abandoned outpost the bounty hunters have holed up in. that abandoned outpost isn't unique - when i arrived on Ixyll II and started following this quest, i immediately recognized it, because i had run into the exact same building layout only an hour or two ago as part of a procedurally generated quest that i did for some quick cash since it was already on a planet i needed to visit anyways.

every room, every bunk, every crate of ammo, every safe tucked away under a desk, it was all familiar. the stuff inside the boxes might be different, sure, but i'd seen everything this building had to offer already, even though i generally avoid going out looking for meaningless busy work over and over. if i visited every meaningless proc-gen moon, i'd expect to start running into this type of repetition sooner or later, but this was me following up on a side quest with named characters, unique dialogue, and an interesting narrative hook that i thought was worth pursuing. when you can go out of your way to try and discern what planets actually have something unique in such a vast galaxy and still run into repeated content, it creates a sense of doubt in me as a player. it makes me a little less likely to go out of my way for things, a little pickier about where i land, a little more likely to just grav-jump straight to the game's handful of big cities and skip over everything that's not on my immediate path.

to start using it as a counter-point for what i find flawed in Starfield, let's look to Fallout: New Vegas again. that game has, relatively speaking, a small map - still pretty big, all things considered, but much more tightly packed compared to contemporary Bethesda releases. there might be less of an incentive to just point yourself in a direction and start walking, but the benefit is that there's basically no wasted space anywhere in the Mojave. everything is placed with intentionality and artistry. the Deathclaw-infested Quarry Junction is used as a chokepoint to encourage players to take the long way to the Vegas Strip, which means you're stumbling through places like Primm and Novac where you're meeting interesting people, picking up exciting quests, and taking more time to learn about the world and shape your opinions as a denizen of it. you'll probably run into the NCR and Legion at some of their smaller outposts throughout the southern edge of the desert, which means you'll have hands-on experience before you can reach their bases of operation and start making big decisions about what sides you're taking in their ideological and military conflicts.

in-house Bethesda games, on the other hand, are obsessed with scale, particularly scale that can be quantified in some exciting way like "1000 planets". they are the original progenitors of the "See that mountain? You can climb it." school of game design. it doesn't matter if the mountain is worth climbing - it matters that it's there and that you could decide to do it, and that there's a loose framework of combat and looting to make you feel like you got something done on the mountain. even some of the larger mechanical additions they've made to more recent games, like outpost building, have a similar weightless feel, where the act of being able to do a thing is considered novel enough reason to do it. cards on the table - i didn't build a single outpost in my entire playthrough of Starfield. it is, thankfully, pushed a lot less hard than in Fallout 4, where the system already sucked to begin with, but now it just seems kind of vestigal, and most of the major benefits you get out of it seem to just feed back into making more outposts.

all of this still isn't really surprising, though, is it? like, of course they did it this way. i might prefer a tightly crafted world of, say, a handful of star systems that each have uniquely crafted worlds that only use light touches of procedural generation to fill out the wilderness, but i'm not shocked that Bethesda went big. going big is kind of their entire brand and expecting them to meaningfully dial it back at this point is a bit of a fool's errand. if all i had to say about Starfield was a debate between the merit of small hand-crafted worlds vs. algorithmically driven grandeur, i don't think i'd be here writing about the game.

what's really made me want to talk about Starfield is the writing. if there was anything particularly exciting about yet another Bethesda game beyond the window dressing of a new genre, it was the fact that they haven't created a new universe since before i was even born. Bethesda's writing is... let's say hit-or-miss, but generally in a way where i get really invested about how they failed or succeeded. the biggest example of this would be their last game before Starfield, Fallout 4. when that game first came out, i didn't really mind the story too much because i didn't have much outside context to compare it to, but having now played New Vegas, i actually have some extremely strong opinions about how much Fallout 4 fundamentally misunderstands the core appeal and potential of that franchise.

as cheesy as it feels to say this, Fallout at its best is a story about society. in the wake of petty squables leading to nuclear armageddon, civilization rises from the ashes, and i think the fundamental driving factor that i see in that setting is how it explores human nature. the citizens of the United States, before the bombs dropped, lived in a simple retro-futuristic world of good guys vs. bad guys, spurred on by propaganda and rampant consumerism. as civilization finds its footing again, the Earth is inherited by all sorts of people, whether they've lived their entire lives on the ruined surface or been unwitting guinea pigs within the Vaults. Fallout interrogates about how people should guide the future of society in the wake of global annihilation - how much should these new civilizations emulate the ones responsible for the apocalypse? how do traditions change when handed down from the old world to the new? war might never change, but how do the people who fight it?

Fallout: New Vegas carries these themes on masterfully. when i described the game as 'post-post-apocalyptic' earlier, that wasn't a typo - it's set 200 years after the bombs dropped and it actually feels like it. the slate was wiped clean, but it's had time to become populated with all sorts of burgeoning new civilizations, and the game's main factions all represent facts of how the old world impacts the new. the NCR seeks the glory of the old United States and commits to some classic imperialist overextending and annexing to feed that fantasy. Mr. House is literally an old world capitalist dedicated to self-preservation, cloaking his autocratic ambition in the same kind of futuristic promise that fueled Vault-Tec. the Legion give off the outward impression of just being flat-out terrible, and they are, but Caeser has a surprising amount of keen foresight into history and sociology and pragmatically uses ancient Roman iconography as a model to motivate and enforce his violent reign.

Fallout 4 is about... i dunno, how cool the apocalypse is? it's basically an isekai, except for the parts where it isn't. on the one hand, you're more detached from the world around you than ever - your player character was frozen as the bombs fell, so you have to learn the ropes of what's up in post-apocalyptic Boston from square one. one of the biggest instances of this ludonarrative dissonance comes from the currency in the game. i, the player, know that bottle caps are the de facto currency of Fallout, but in-universe, why would someone fresh out of cryogenic sleep know to start hoarding those things like crazy? you could say that if i care about roleplay, i could choose not to engage until i feel like my character would understand that, but i would say that games like New Vegas demonstrate that you can start the character out as an existing citizen of the setting who'd understand these things and still make the player feel the drive to learn more about the world at the same time. you can absolutely create compelling opportunites for roleplay in your role-playing game without asking that the player simply disengages from entire systems to feel immersed.

then, on the other hand, there's Bethesda's ever-present urge to make sure the player feels important. in Skyrim, you were the descendant to an ancient lineage of dragons. Starfield, in its own way, has a similar hook that i'll go over later, where you're immediately thrust into becoming a Very Significant Person. Fallout 4's hook is that you had a spouse and child before the apocalypse, and that someone has mysteriously stolen your baby boy from his pod. this winds up being a real mixed bag for the storytelling. it's refreshing that you're not given some kind of fundamental power that makes you better than other people, yes, but it also makes getting in your character's shoes incredibly hard. want to go out and explore the Commonwealth like Bethesda clearly urges you to? alright, but don't forget you're also a parent who's ignoring the single-minded search for their child! have fun!

the game does very little to meaningfully play with the themes that drive Fallout. there's sort of a throughline of how you can't live your life stuck in the past, i guess, but the broader sociopolitical implications of armageddon are pared way down and the game mostly uses Boston as set dressing, making some skin-deep connections to how the good guys rebuilding society are kind of like the Founding Fathers or whatever. it devolves into a bunch of stuff about androids replacing people and your son being the twist villain or whatever, but none of this feels like it's really got a point.

sometimes, i see people say Fallout should move outside of America for its next game, and i vehemently disagree, because i think the specific framing of post-WW2 American paranoia informs so much of what makes Fallout, from the big picture stuff like world design right down to the smallest details. if you've only happened to play the in-house Bethesda games, though, i can see how you would come to the conclusion that the real-world settings are just novelty flavors of the month draped over a generic post-apocalyptic frame.

another reminder, then, that Fallout: New Vegas handled all of this a million times better, and managed to make the player feel important without making them some kind of supernatural being or giving them a hard-coded emotional throughline. you're just a courier who was in the wrong place at the right time. the game proposes a driving question - 'why'd that guy shoot me in the head?' - but how you feel about that is up to you, and your significance in the Mojave conflict is much more of a slow burn as you come to understand the true importance of the delivery you were making. by the end of a playthrough, you'll have shaped the future of New Vegas, but not because you became the living embodiment of your faction of choice. you're still just a courier, with a very literal bargaining chip that everyone wants, and all the opportunity in the world to decide who should get it.

...wait, crap, i started this whole thing because i wanted to talk about Starfield, didn't i? let's back up a little bit.

Bethesda's lackluster handling of what makes Fallout such an interesting world might be in part because it's not a world they crafted themselves. they inherited it from Interplay, and New Vegas was put together by people closer to that original process, who had a tighter grip on why someone felt compelled to create that world in the first place. what kind of bold new vision have the minds at Bethesda Game Studios fashioned when given a new blank canvas? it certainly skews closer to something like Fallout than the outright high fantasy of The Elder Scrolls, which is great, because it means i don't feel compelled to go play Skyrim to start drawing specific points of comparison, although i'm sure it'll come up in broad strokes.

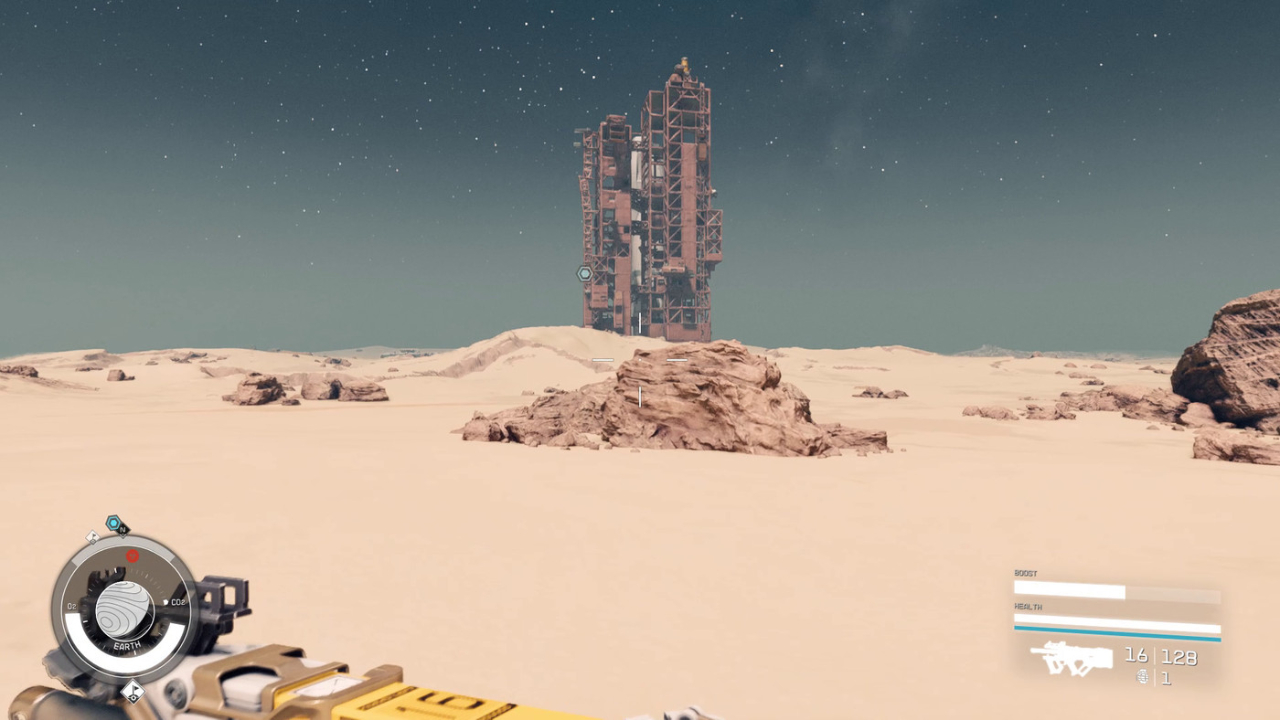

if i had to try and describe what Starfield is about, in a broad tonal sense without digging into the actual meat and potatoes of the plot, i would say it's a game about human curiosity and the innate, intangible drive towards understanding our universe. it poses questions about the risk and reward of seeking out new knowledge, of what drives people to explore, and what a world where humanity has outgrown a dead and decaying Earth might look like. a term coined by the development team for the game's aesthetic that also serves as a useful compass for parsing its message is 'NASA-punk' - the game does start dipping into questions of extraterrestrial life and leans more and more into the 'fiction' side of sci-fi as it progresses, but it's starting from a baseline of practical, utility-driven space travel in a world where humanity hasn't found signs of anything else sentient out there in the cosmos.

outside of being a guiding principle for the game's aesthetics, though, i think the 'NASA-punk' thing really speaks to what they were trying to do with this game's story. this is, absolutely, without a doubt, a game written by the type of guy who laments that America stopped sending guys to the moon. the plot of the game opens with you working a mining job for a mysterious client and uncovering a strange Artifact (proper noun) that shows you grand visions of space and music. this client, as it turns out, is a member of an organization called Constellation. they're the 'last true explorers' in a world where space travel has become normal, boring, and routine, living in a sort of X-Men-esque mansion and solving cosmic mysteries that the local governments have neglected. your experience with the Artifact is enough for the client, Barrett, to immediately entrust you with his starship and robot so that you can head to the United Colonies capitol city of New Atlantis and become a member of Constellation yourself.

the entire opening is rather hectically paced, almost certainly with the intention of getting the player to The Good Stuff as fast as possible, and i look forward to its long introductory elevator ride becoming as infamous as the Skyrim wagon one day. aside from however long it takes you to create your character (very, in my case), the whole sequence takes maybe 15 minutes tops and immediately primes you as Very Significant for having your cosmic experience, enough so for a complete stranger to hand you the keys to his only way off the planet. with how the game then funnels you into a fairly expansive tutorial on the lunar surface of Kreet, it's easy to lose sight of all that big picture stuff for a while.

while we're talking about the introduction to the game, i will absolutely give Bethesda props for walking back some of their decisions from Fallout 4. yes, you are invariably a miner at the start of the game, and you will invariably experience some kind of awe-inspiring celestial awakening, but the character creator does have a fairly robust set of backgrounds and traits for you to choose from. these mostly end up affecting statistical stuff and what skills you'll start off with, but it's closer to roleplaying than anything in Fallout 4, and the stuff you choose does occasionally come up as an option in dialogue. i chose the Diplomat background, since it had useful skills in speech and commerce, but i also took on the Wanted trait, meaning my character had accrued a mysterious bounty before i took control. they were also an introvert and happened to inherit a dream home on the planet of Nesoi. in the time-honored tradition of filling in the ludonarrative gaps, i imagine Captain Tallahassee was a diplomat of sorts, but perhaps more of a blue collar mediator aboard a cargo freighter than an upper-crust government official, settling the tensions of interstellar travel with a silver tongue rather than an electron cannon. one thing that helps with that level of player-driven background detail is that Bethesda has also ditched the 'voiced protagonist' angle from Fallout 4, making it much easier for writers to create more dialogue options and for players to insert their own tone and motivation into their choice of words.

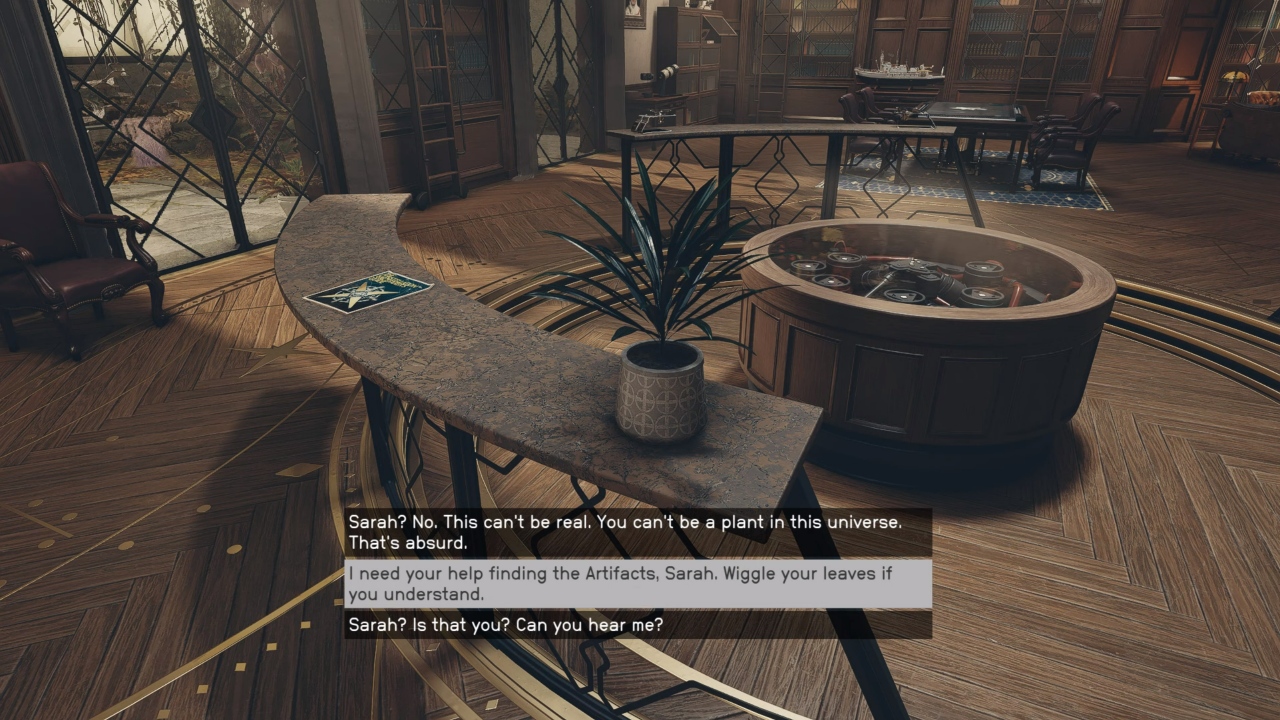

after a few hours of learning the ropes of gameplay on Kreet and putting my persuasive skills to work on the local pirates to avoid a full-blown gunfight, it was finally time to head for New Atlantis and get properly acquainted with the main cast of the game. Constellation is an eclectic mix of personalities, such as the socially awkward theologian of the group, Matteo, who provides a uniquely spiritual insight into what is largely a practical science-driven organization, or Walter Stroud, a CEO who would rather put his bank account to work funding something interesting than just sitting on his fortune until he dies. the one who ultimately takes point on inducting you into Constellation and becomes your first of four potential companions, though, is Sarah, a former UC military navigator who turned to Constellation when her space exploration division was shut down and eventually rose to leadership of the guild.

when you're first introduced to Sarah, you have a myriad of traditional Bethesda-style "woah, you're telling me, Normal Space Person, that i'm now Important Space Person?" dialogue options to pursue, but one way or another, you're ending up in Constellation. each of the four companions has a mandatory quest where you'll tag along with them and follow leads towards more Artifacts, and Sarah's quest is the first of these, taking you into our own solar system to do a little detective work on Mars. when you talk with her about this mission, she brings the conversation to a pretty abrupt halt to deliver this chunk of dialogue, which i'll just go ahead and quote in full -

PLAYER CHARACTER, OPTION 3: What do you mean? You don't care if I steal as long as I don't get caught?

SARAH: I mean Constellation has a roster of members who haven't always been on the "right" side of their respective society. We're risk-takers. Some of us have seen the inside of a jail cell, more than once. If you join us, it means you're committed to our mission. In exchange, we give you latitude in your choice of means.

- and this exchange... breaks the game in half, a little bit? cuts right to the core of a lot of issues all at once? we're going to spend a lot of time unpacking what this one means and how the entire rest of the game doesn't really live up to the tone being set here, but for now, i'll just start with the immediate impression i got and not the long-term implications. my gut reaction to this was that this conversation snapped me out of any sense of immersion i felt inside Constellation's ranks. this was not Sarah being frank with me about the nature of Constellation as a diverse organization, with a common cause that transcends being worried about doing things strictly by the book. this was Todd Howard himself (or, if we want to be accurate and not silly, long-time Bethesda head writer Emil Pagliarulo) reaching through the screen and grabbing me by the shoulders to say "LOOK, CONSTELLATION IS THE MAIN QUEST, YOU CAN DO WHATEVER YOU WANT AND THE GAME'S NOT DESIGNED FOR THEM TO KICK YOU OUT, YOU'RE GOOD TO NOT GIVE A SHIT". even if it weren't for the fact that Sarah ends up being the most outright 'lawful good' companion in a group full of people who get antsy about you doing any crime, this moment would still boil down to Starfield dropping any artifice of its storytelling, just to reassure people who are only here to game that the underlying systems fundamentally can't punish you too hard or lock you out of anything based on the choices you make.

not exactly helping matters when it comes to trying to immerse yourself is how impenetrable the lore of Starfield can be for a beginner. the game signals some of its broadest strokes early on - some of the traits you can choose in the character creation process are background information like where your character grew up or their religious beliefs, but i avoided all of those because, well, i'd never played Starfield, had i? how am i supposed to know if i prefer the United Colonies or the Freestar Collective without any prior context? when it comes to starting a player off in a story, especially when it's been so long like it has been for Bethesda, i think it's important to give your audience some shorthand for what the big factions' respective deals are. case in point, Fallout: New Vegas - the game's world design subtly guides you through an NCR outpost suffering from resources being spread too thin, a town that's been overrun and burned to the ground by the Legion, and the outskirts of Vegas where you can literally see Mr. House's wealth and protection cut off in the form of a wall around the inner Strip. no matter what you do or how long you stick around to ask questions, you're going to form an impression of these major players in the Mojave.

Starfield understands that this type of environmental storytelling is good and useful for onboarding new players, but it stumbles in one critical area. as an example here, your first mission with Sarah starts by asking the local UC Vanguard recruiter about a troop who's run into some trouble and also happens to be in possession of an Artifact. the recruiter, Commander Tuala, immediately tries to sell you on the idea of joining the Vanguard, giving us our first hints that United Colonies citizenship is granted based on volunteer service with a particular bias towards military service. that, to me, sounds abjectly horrifying, and i'm not a fucking cop, so i'm never going to do any of that. the thing is, though, that according to impressions i've seen from other players, the UC Vanguard questline is actually one of the best ways to get a crash course in the lore of Starfield, learning about the recent war between the UC and the Freestar Collective, with details like why and how that war was fought.

the worldbuilding of Starfield's biggest flaw is that it assumes you'll be interested in doing certain things and gates information behind them. if you don't want to be a cop in this role-playing game, you're just going to have less access to the history of this world and you're going to be spending a lot more time piecing things together based on passing mentions. the Colony Wars, in-universe, only ended about 20 years ago, and yet i kind of have to play my character as if they've never heard of this major historical event, because i've never heard of it and the opportunities to learn about it are put behind choices that neither me or my virtual avatar would have any interest in taking. Starfield is designed to guide you to places where you might learn a thing or two, but it feels like everybody in the writing and design process just assumes players aren't going to have any firm ideological beliefs and hang-ups about major institutions.

to me, it seems like Bethesda doesn't want to fathom the type of player who doesn't want to be a cop, because they're approaching this from the lens of someone playing a video game and assuming players just love picking up as many quests as possible. in a vacuum, that wouldn't be a dealbreaker. i still play Halo and care about its characters, even though i know that if the UNSC and Spartans were real, i'd be protesting against them. the difference, though, is that Halo is a linear story, written and told just one way without player input. Bethesda prides themselves on their vast, immersive worlds that players can truly live in, but when they finally develop a fresh exciting new IP for the first time in thirty years, it feels like it's hard to start finding your footing and immersing yourself in that universe unless you either don't detest the Vanguard or are willing to check your baggage at the door, immersion be damned.

what really exacerbates this issue is that, of the four major faction questlines in Starfield, at least three of them are this unapproachable for my tastes, if not all four. we've been over why i don't want to join the UC Vanguard, the Freestar Collective questline seems like largely the same thing with a bit more of a libertarian cowboy angle, and i find it hard to justify climbing the corporate ladder with Ryujin Industries whether that's in-universe or just my own personal opinion. for someone like yours truly who's not especially fond of police or mega-corporations, that leaves only the Crimson Fleet, and... well, we'll cross that bridge when we get to it. you could say the point of roleplay is to be something i'm not, or just accuse me of overthinking these options, but, again, New Vegas comes into play here, because that's a game that actually feels like it accomodates a wider variety of viewpoints. not only are there more factions in that game who represent the common citizens of the Mojave, but it was also easier for me to think pragmatically, to pick and choose when i helped the NCR push back the Legion and when i undermined their efforts to annex the region.

enough about faction quests i'm missing out on, for now, though. the first act of Starfield's main story keeps chugging along, giving you lots of reasons to visit various regions of space and plenty of one-on-one time with your new Constellation companions. for what it's worth, i don't dislike most of the crewmates this game gives you, for the most part. Barrett doesn't leave a strong first impression when you're being rushed through the introduction as fast as possible, but once you start working with him in Constellation, i think he works well as almost an aspirational figure, the type of explorer i wanted my character to develop into. he's the type of guy who'll get kidnapped by pirates and then make friends with them by telling old stories about the furthest reaches of space and the nature of quantum physics. he's been everywhere and dabbled in a bit of everything, he's charming and easy-going, but there's still some depth there too, as you help him process the death of his husband and start looking into some mysterious loose threads that death left behind.

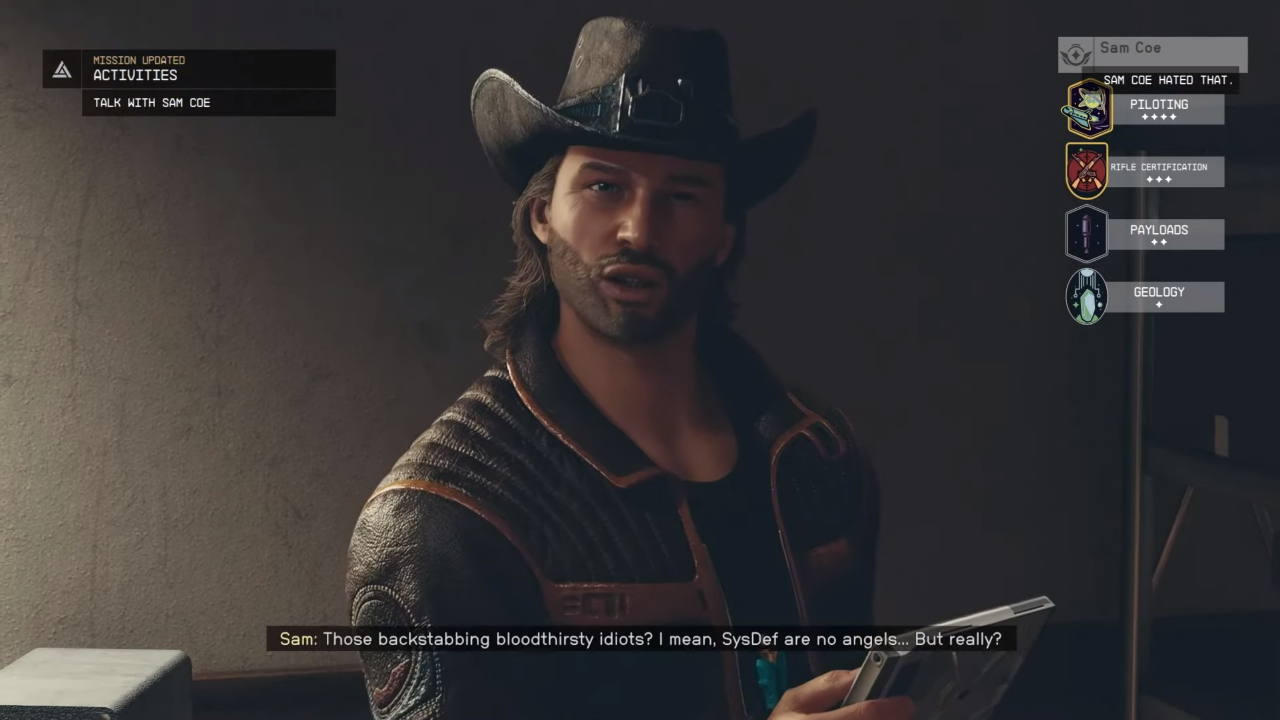

Sarah, who we already covered a little, is easily my least favorite of the four major companions, with her ex-military background definitely shining through a little more often than i would like. again, it's bizarre to me that she's the one who delivers the speech on Constellation running by their own rules, because she's the quickest to chide you for going off the straight and narrow path. the other two companions who you don't meet as immediately are retired cowboy/divorced single dad/heir to an old-school pioneer fortune Sam Coe, and the mysterious Andreja, who's introduced in the midst of assassinating a local space cultist and takes the longest time to truly open up to the player. i don't know if any of these characters will really stick in my head in the same way companions like Veronica and Cass from New Vegas have, but they're all interesting enough for me to bother interacting with. i even managed to finish Sam's personal arc and help him have an honest emotional dialogue with his ex-wife, namely because i was so sure that he was gonna be the one with the dead spouse and i was pleasantly surprised when you find out he really is just divorced and he gets super real with you about it.

once you've had time to get acquainted with your new co-workers and seen more of what the galaxy has to offer, the next step of the mystery opens up, as it becomes clear the Artifacts are connected to a separate set of gravitational anomalies across the cosmos, leading you to ancient temples that clearly weren't constructed by any known human civilization. some of these temples are at set locations with curated setpieces to accompany them, but a lot of them are also randomly seeded throughout the galaxy on each playthrough, and since this is the most relevant time to get it off my chest - i honestly cannot believe Bethesda put these damn things in the game 24 times. there is only one temple puzzle, for all 24 temples, and it's literally to fly through hoops in zero-gravity environments. it never gets any different, the hit detection on the hoops is so imprecise, and sometimes the puzzle fakes you out by making you think the hoop is spawning one place and then shifting it once you start moving towards it. i wouldn't feel the need to put such a fine point on it, but again, they put this same thing in the game 24 separate times, and for a game that's supposed to be about the sheer majesty of space and the unknown, you'd think the main plotline should involve a more compelling puzzle than flying through hoops, an activity which we all still compare to Superman 64 to this very day.

anyways, get good enough at flying through hoops and you're granted space magic! indeed, these temples and the abilities they grant are basically just this game's equivalent of Skyrim's various Dragon Shouts. i'm not crazy opposed to this aspect of Starfield, but my first impression of the entire Artifact plot was that it was a pretty boring by-the-numbers ancient aliens thing, and the rewards feel so much like Elder Scrolls-style magic that mechanically, it felt grafted on from a different game. the abilites are neat enough - i particularly enjoy creating a low gravity field that makes my enemies hover helplessly into the air - but they're not meaningful enough to really shake things up and they end up feeling a little auxillary to the whole Starfield package.

since we're at a bit of a natural act break in the main story, now feels like a good time to start talking more about the game's side quests. i don't feel like i can really grade them as a whole, but if i had to try, i would say they did... fine? the game does a decent job of signposting things by having you naturally accumulate 'activities' just from overhearing NPCs talking while you're doing other stuff, so even if this game's stuffed to the brim with procedurally generated content, it's not too hard to go find the stuff that actual human quest designers made on purpose. as i brought up early on with the Eleos Retreat example, it can be hard once you're knee-deep in a quest to know how intentional its design aspects are, but there's a decent amount of places that at least start with a unique prompt and give you something to do.

one of the first big side quests i wound up pursuing, and one that i think left a bit of an unfortunate impression on me, was heading to Paradiso and dealing with the ECS Constant. Paradiso exists out on the fringes of civiliziation as a kitschy resort planet, decked out with palm trees and the kind of kitschy iconography that wouldn't look out of place in Fallout. it also happens to be one of the few major settlements that isn't associated with the United Colonies or Freestar Collective, instead hiring a private security firm to enforce the will of the board of directors thanks to some old treaties they're still taking advantage of. when you arrive, there's a massive unidentified ship in orbit, which only broadcasts static when you try to communicate and doesn't match any known make or model. the security team on the surface, in classic Bethesda fashion, drop the problem in the lap of the first person who walks in, and ask that you try not to make a big deal about it so that the resort guests don't get scared off.

the true nature of the ship, and the reason it's unidentifiable, is that it's a 'generation ship', launched from Earth before the invention of the grav drive allowed for quick interstellar travel. the ECS Constant has only just now caught up with modern society and arrived at the planet of Porrima II, which they believe they have a right to colonize, as was their forefathers' mission. they ask you to be their representative in negotiations with the Paradiso board of directors, and you're sent back down to the surface in the hopes of cutting them a deal, with Captain Brackenridge emphasizing she isn't really looking to back down about claiming sole ownership of the planet, even if there's room to share.

so, i head back down to Paradiso and i'm sent up to the top-level suites to negotiate. i already have full clearance to do this, but there's a unique NPC at the reception desk - name, personality, voice acting provided by Casey Mongillo from that Netflix dub of Evangelion - who stops me to make sure i'm on the level. it's a bit of flavor to prep for the meeting, i guess, but when you put someone unique like Keavy in front of me, and have them tell me about their struggles of working as an underling to the board, gears start turning in my head.

i head into the boardroom and the directors are like, cartoonishly evil about all of this. there's the one guy in the room who says maybe it's bad to propose making the crew of the Constant work at the resort as indentured servants, but the other two are fully committed to maximizing profit and the CEO even muses about how he wishes the Constant just didn't exist and how oh-so-terrible it'd be if their ship just happened to blow up in a tragic 'accident'.

so i'm alone, in a locked room with a group of ghoulish caricatures of capitalists looking to enslave or kill innocent people, with the only remotely good offer being that i pay the five-figure fee to install a grav drive onto the Constant. i'm alone in this room with these people. and the receptionist out front doesn't seem awfully happy with their job. so, y'know, i start blasting. why does a video game have a disgruntled employee out front if not for me to have an alibi when i attack their bosses? man, wouldn't it be a funny and interesting conclusion to this side quest if you had this tropical resort for yuppies being occupied by a bunch of people who've only lived inside one old ship for their entire lives?

ah, wait a minute. the CEO just kind of stumbles over for a minute and then gets back up. i have a bounty applied to me, but the game seems to have trouble actually getting guards sent up the elevator to the executive suites, so everyone's kind of scared, but they just reset and start talking to me like nothing happened if i stop shooting for half a minute.

enter the 'essential NPC'. Bethesda likes to deploy this concept a lot in various ways, and it seems to only get more constrictive with each new game they put out. Morrowind had its famous 'thread of prophecy' that allowed you to kill NPCs, but gave you a sort of in-universe warning that this save would be softlocked and unable to progress in the plot if you happened to kill someone who was necessary to the story. twenty-ish years later in Starfield, this manifests as certain people just... not dying. attack as much as you want, they're just a little winded, they'll be back up in a second. they'll be mad at you, maybe, but they'll still talk to you like nothing happened if you wait it out. the definition of 'essential' continues to become broader and broader, too. Paradiso is not crucial to any part of Starfield's main story. it's entirely optional and i only ever encountered a handful of fetch quests that asked me to go pick something up there.

i'm not saying the quality of an immersive RPG absolutely hinges on your ability to solve problems violently. it's, generally speaking, not my first approach - i almost always focus my talents into charisma or whatever the game's equivalent stat might be, for a variety of reasons, namely that i think it can lead to more interesting problem-solving and allows me to do things that non-RPG games can't. to once again draw in Halo, all my action verbs in that game are always going to be fighting and shooting, and that can also be the case in Bethesda games, but they give me the opportunity to take different approaches to situations.

charisma-heavy does not always mean pacifist, though, and sometimes, when i put myself in my character's shoes, yeah, i think they'd solve the problem with a little blasting. sometimes that's just on me, but sometimes it feels like the game has been giving me cues that make me think that's a potential solution. when it turns out i was wrong, and that all the solutions just suck, and when the game stops to go "no, you can't kill this person who's only involved in this single quest, that'd be going off-script", it pulls me out of my investment in the fiction like nothing else. and hey, guess what game i'm about to bring up that avoids this issue entirely? a Bethesda-style RPG that doesn't do the whole 'essential NPC' schtick, that was carefully planned like a fucking Rube Goldberg machine by a team of talented writers and engineers, working in invisible clockwork so precise that you can kill the game's main antagonists halfway through and it'll not only let you keep playing, but react and adapt to accommodate for the choices you've made? a game that did all this on a much more primitive iteration of Bethesda's in-house engine, developed in just barely over a year, literally over a decade ago?

you can argue that Fallout: New Vegas is so particular in its attention to detail that you can't really do it again. it requires a very specific approach to game design where you make sure you have every possibility checked and thought out before you start laying down the digital foundation. it requires a smaller, tighter world than the type of thing that's made Bethesda famous enough to keep justifying these triple-A productions as they start to take almost entire decades to produce. it requires writers who are going to have to stretch to cover up some of the more extreme oddball variables the player can throw into their plot. i'd agree with all of this, it seems incredibly hard to design a game in that way, and i'm fine if not every game goes all in on that philosophy. at the very least, though, you would hope that even a little something from New Vegas might have rubbed off on Bethesda, that they might just consider the idea that not every named NPC in the game has to be treated like they're as essential as the main characters.

i bought the grav drive and haggled it down to 25,000 credits. i was able to visit the ECS Constant one more time to start a follow-up quest about one of the inhabitants wanting to leave the ship. Captain Brackenridge said i needed to bring her 50 potatoes to cover for the loss that the ship's farming department would take from losing a worker. then the ECS Constant just... vanished? it seems like it's supposed to appear randomly to reflect the idea that they're now grav-jumping across the galaxy looking for a new home, but the waypoint is permanently stuck in orbit over Paradiso with no ship to be found. fun. let's go back to the main plot, i guess.

your next big stop is an unlikely pairing with Walter Stroud as he brings you into Freestar Collective territory, to the planet of Volii Alpha, in order to use his company's funds to secure an Artifact from the shady underbelly of Neon. it's a really easy setting to get lost in and i guess it's, by default, kind of my favorite of the game's few major settlements? it feels the most tightly packed and tonally cohesive, with all kinds of errands you can run, whether you're getting tangled up in the city's various gangs or helping its shopkeepers unionize against the corrupt security department. in a game that already feels subtly cyberpunk upon close examination, Neon just brings all those genre influences right to the surface. it's wildly unsubtle, there's nothing especially original about it, but it works well enough. maybe because i didn't play that other cyberpunk game, the one with the capital C and everything?

it's a fun quest that involves a bit of high-level corporate intrigue, balances out persuasion checks with combat sequences, and gives you time to soak in the atmosphere of the game's most atmospheric city. plus, you get to embarrass a CEO a lot in front of his girlboss wife, so that's cool. after i wrapped things up getting the Artifact, i spent a lot of time doing side quests in Neon, which made it a real shock when i remembered the quest wasn't completed yet. as you jump to orbit, you have your first encounter with the enigmatic Starborn, who arrives in a distinctly alien ship and warns you to stop your quest, saying that you're playing with cosmic power you couldn't possibly understand. from here on out, whenever you hit up a temple and obtain a new power, one of their all-powerful representatives will appear, menacing you with space magic not too dissimilar from your own and yelling vague hot air about 'glimpsing the abyss' or whatever. it's an interesting enough wrinkle, and that first frantic grav jump to narrowly avoid a confrontation with a clearly superior opponent does have some nice tension to it.

the addition of some kind of outside force tied to the Artifacts definitely sends ripples throughout Constellation, with some fun ongoing side conversations about the guild debating whether the Starborn are aliens or time travelers or something else entirely, but aside from ramping up the stakes and giving the crew a bit of doubt, it's pretty much business as usual. collect Artifacts, fly through hoops, kill Starborn guardian, earn all kinds of space magic like precognitive abilities or the divine power of insta-mining. eventually, you reach a point where the game gets weirdly strict, strict enough that i could immediately sense something was cooking in the background, as Constellation's satellite operator Vladimir takes approximately half the cast with him to do space station repairs while insisting that i have to do this next mission with Barrett.

much like most things in Starfield, it's not exactly original per say, but it is a decent enough deployment of standard sci-fi tropes, as you and Barrett head off to visit the eccentric collector Petrov, who's come into possession of an Artifact. a little persuasion here, a little 'shooting Petrov in the leg and getting him to surrender' there, and we're one step closer to the mysteries of the universe. we're also one step closer to whatever reason the game decided to make sure the characters were split up, but thankfully, before that ticking time bomb can go off, you get arrested! rad!

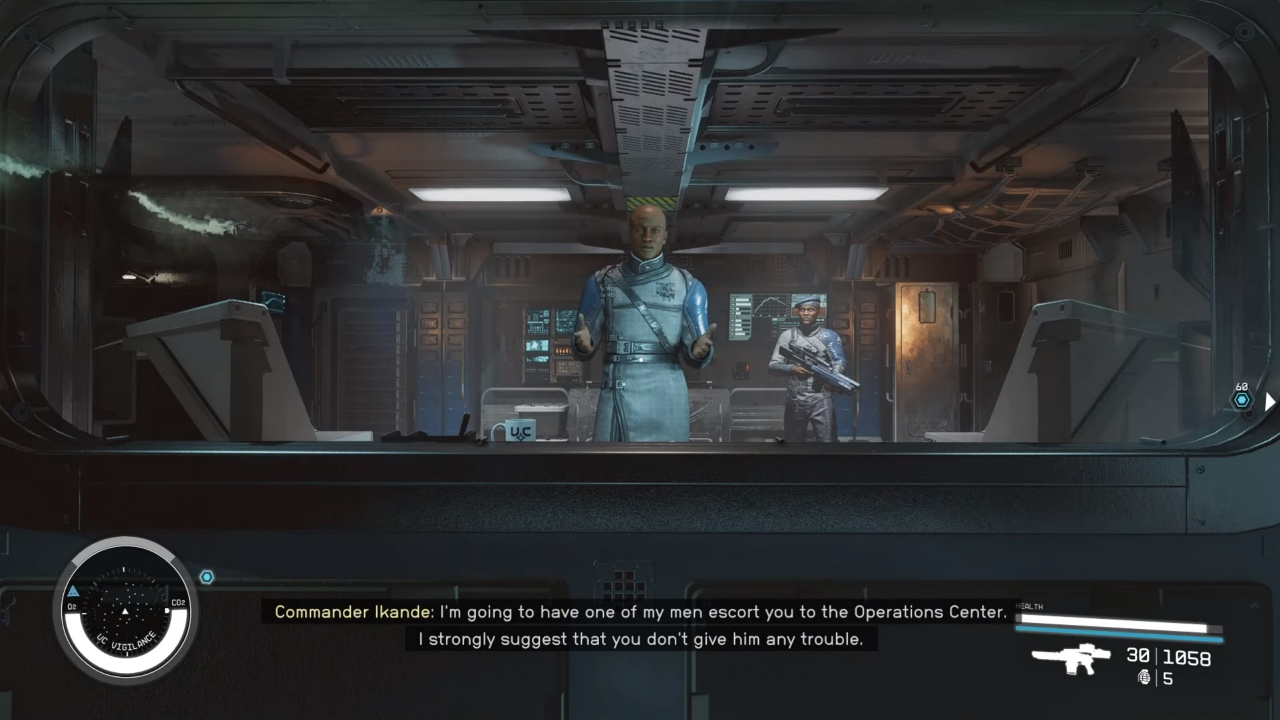

this brings us into the fourth faction quest, and the only one i actually played through, with the Crimson Fleet pirates. my understanding is that any type of bounty on your head will eventually queue you up for this particular opportunity, and the heist with Petrov just happens to be the point where the main quest unavoidably puts a bounty on your head - all unrelated to the other bounty i have from taking the Wanted trait, of course. you see, you've caught the attention of the United Colonies' SysDef department, a task force specifically dedicated to dealing with piracy and space crime.

yes, even the faction quest about joining the pirates in this game is somehow a cop thing, because Commander Ikande thinks that you have what it takes to infiltrate the notorious Crimson Fleet on SysDef's behalf, and he's willing to blackmail you until you agree. it's time to go be a narc.

i will be gracious to Starfield here and admit a little bit of metagaming and misinformation took place on my end. i knew, loosely speaking, what the four big factions with full subplots were, and i knew i would probably only be interested in doing the Crimson Fleet stuff, if anything. somehow, in spite of me not jumping on the special early access edition, it still seems to have taken a long time for people to figure out how this particular side quest can actually start. i did a bit of research and at the time, everything i was seeing implied that joining the Fleet as an undercover cop was your only inroad. it's since come to my attention that you can put your foot down a little more and your cellmate will instead lead you into the quest, but for reasons i'll get into as we unpack this chain of events, it's a bit of a zero-sum game.

one of your first major assignments once you've gotten a contact with connections to the Crimson Fleet is to prove your loyalty by doing a favor for the pirates' second-in-command, Naeva Mora. the last guy she jumped into the Crimson Fleet decided to back out on them, and she wants him dead, having finally tracked him down to a new position working on a medical supply ship under an alias. even outside of whatever your own personal feelings might be, Commander Ikande has emphasized that even if this is a high-stakes undercover operation that his entire career hinges on, he really, really doesn't like you killing people, so you have a vested interest in not doing that.

i, personally, have no real skin in the game about whether this guy lives or dies, but ideally things shouldn't have to get too messy, so i decide going in that i'd like to try talking this out. the captain of the ship steps forward and resolutely refuses to hand over his crewmate, no matter what his pirate background might be. excitingly, the game even lets me use that Wanted trait to pull out some unique dialogue about how i know what it's like to live on the run! that's almost starting to get close to some actual roleplaying informed by the character i chose to create!

unfortunately, no matter what i tried, across multiple quicksaves and using my cosmic power of precognition to read what every response might be, i think Austin Rake can only be dealt with in... let's say two-and-a-half ways. you can just get in a fight with the entire crew at once, whether by shooting first or failing to win them over in a persuasion check. you can convince the crew that they need to gang up and kill Rake to save themselves. or, in the only peaceful outcome here, you can hatch a scheme with the captain to get Rake out of harm's way... and into a maximum security SysDef prison cell.

the game gave me a thing i could say because of the Wanted trait, but it doesn't actually feed into any unique solution for the problem. Captain Tallahassee cannot use their criminal wit and smooth-talking charm to help Austin Rake out of this jam. you are either full-blown okay with murder, or full-blown okay with putting this guy in jail for life, under the watchful eye of the Space CIA. this disappointing choice really set the tone for a lot of what was to come with the Crimson Fleet quests - i don't think it ever got so unnecessarily binary like this again, but it speaks to a deeper underlying issue with how Starfield has a blunt, inelegant approach to 'making the tough decisions' like that.

as if to twist the knife a bit more on all this, your first mission as a proper pirate of the Crimson Fleet is to accompany the leader, Delgado, on a mission down to an abandoned United Colonies jail facility. see, the Crimson Fleet didn't get its start as just a powerful crime cabal or a mafia-style family - their original founder, Jasper Kryx, was a notorious pirate, locked up and treated like an animal under the surface of a barren, frozen world. the Fleet, as it stands today, is the result of a prison riot Kryx led about 100 years ago, overtaking the control station in orbit over Suvorov and establishing a code of solidarity and honor between disparate thieves.

sociopolitical implications aside, it's a really fun quest, leading you through an old abandoned prison as part of Delgado's obsessed search for Jasper Kryx's final lost treasure trove, accompanied by a fellow new recruit who immediately jumps to the idea of killing Delgado together in a way that leaves you wondering if he's there to test your loyalty or if he's just that reckless and dumb. but, sociopolitical implications back to the front for a moment - i think this wrinkle in the Crimson Fleet's story, this element that they were started as a revolt against inhumane prison conditions, is a great example of an area in which Bethesda's writing falters.

i think the people writing Starfield are at least a little in touch with the world, enough to understand that people have complex feelings about criminal justice and the prison system in the year 2023. if they weren't, it wouldn't be such a recurring undertone of the Crimson Fleet material in this game. no art is made in a vacuum, even if Bethesda's game design can sometimes feel a little frozen in time. you can even visit characters who've been arrested throughout the SysDef operation in the brig and have some conversations with them. the guard up front will stop and have a chat too, opening with a charmingly quirky obsession with cleanliness before pivoting into a pretty harrowing observation about how the United Colonies has treated prisoners too harshly before, but you can't go too easy on them either, wink wink.

to me, i think the heart of the issue is that Bethesda is afraid to have evil in their games, and not out of some sense of self-censorship and good taste. no, Bethesda is insecure about their stories being perceived as overly shallow. if the Crimson Fleet were just pure bad guy pirates, that wouldn't be very deep and exciting in your massive immersive epic RPG world. but they are also, on some fundamental level, still clouded by centrist NIMBY politics. the pirates are people too, and they had a reason for their revolt, but that's about as far as the game goes when it comes to extending empathy and interrogating why crime happens. you have very few options, if any, to meaningfully confront the United Colonies about their part in all of this. the government is capable of messing up and mistreating people and creating their own problems, sure, but fighting the government about it would be fundamentally bad, because clearly the United Colonies are the good guys, because... rule of law, and civilization, or whatever.

and, as with most issues in Bethesda games, we can take a look at Fallout: New Vegas to see how it's done better over there. Caeser's Legion are about as evil as you can get. misogyny and homophobia, pillaging, burning towns to the ground, enslavement and human trafficking, the whole nine yards. they are bad people. you can go and debate Caeser about his ideology, and he'll go on about how he's following in the footsteps of history's great philosophers and conquerors to create a new society that can endure the cruelty of a post-nuclear world, but you can also see firsthand that the man relishes in the inhumanity of it all. the game gives you the option to side with him, but it just hits differently than the usual 'evil Bethesda' faction in some way i can't quite put my finger on. if you wanna side with the evil wizards or the bandits or whatever in other games, sure, whatever, but New Vegas goes out of its way to expose you to so much of the impact of Caeser's deeds that i feel like it says something more about the player for choosing that path, even if it's just a sort of Undertale-esque curiosity to see even the worst ending played out.

one of the great benefits of not shying away from that level of evil is that it lets you start actually unraveling what good looks like in comparison, and not in a toothless "centrist or libertarian" way that keeps popping up in so many of Bethesda's stories. the NCR are on the brink of having a breakthrough in their stalemate against Caeser's Legion, but they're also eager to annex New Vegas and keep manifesting destiny the minute this is all settled. you can trace all kinds of problems in the world back to them, whether it's wasting resources on establishing a police presence in the Strip, or sending mercenaries to a peaceful Super Mutant settlement in the hopes of driving them out and/or justifying a show of force against them. the ways in which you can engage with them, hurting or helping their cause bit-by-bit, and the game's capacity to handle a mixed reputation, creates so much depth. there's a whole side quest about a high-ranking officer who's grown disillusioned with the war and has started falsifying reports back to NCR command in the hopes of getting them to pull back - it's entirely optional, but that guy has like, 11 different endings he can wind up with, ranging from shooting himself in his office in shame to running as an anti-imperialist senator.

there is no such thing as a mixed reputation in Starfield. you cannot change people's minds or the courses their single-minded goals will lead them down. you might get a dialogue option where you get snippy with Commander Ikande and remind him you're not his friend, sure, but that's just another funnel to all the same missions, all the same conversations, all the same accolades about how you're doing the right thing and making the galaxy safer. the kindest thing you can do for the Crimson Fleet in this scenario is getting some of their members out of harm's way by entrusting them to the same oppressive prison system who's failures led to their creation in the first place. even then, that incredibly threadbare sense of sympathy is extended seemingly at random to only a handful of the characters.

then, of course, there's the counter-argument - if i hate SysDef so much, why do i keep working with them? throughout the various steps of helping Delgado assemble a plan to raid a GalBank vault-ship stranded inside a gas giant, it's not too hard to avoid killing people just by nature of how i play the game, so i'm still in Ikande's good graces up to the very end, even if i'm intentionally avoiding handing over too much evidence against the Fleet. by the time i've secured Jasper Kryx's long-lost final score, the game is still telling me i can take it to either of the main factions.

first of all, it's kind of crazy that one of the game's big faction subplots involves you carrying around a space briefcase full of potentially billions of space dollars, and there's no option to just take it for yourself and piss everyone off. right? that feels like it should be a thing, and characters in the game will talk to you like that's an option you could have taken, but you can't, because it's only here where Starfield establishes that all this currency is on the blockchain or whatever the fuck and you'd need a master hacker with SysDef or the Fleet to decrypt your loot.

as for why i ended up holding my nose and taking it back to SysDef? i was trying to meet Starfield on its own terms, i guess. you can choose the Crimson Fleet, sure, and that's what i really wanted to do, and what i felt like my character would really want to do. the issue here is the ways in which the game can and can't actually create consequences for that decision.

obviously, if you hand Kryx's Legacy over to the Crimson Fleet, SysDef isn't going to be happy with that and you'll end up boarding their flagship as part of the final confrontation between these two factions. there'll be fighting and bloodshed and declarations that you're a traitor to the United Colonies. but... Constellation's headquarters are on New Atlantis, so we can't go locking players out of that, right? so you're a traitor, but only the CIA seems to really know or care, because the rest of the United Colonies is still super-chill about you. you can even still sign up for the UC Vanguard! wouldn't want players to miss out on the opportunity to do all the quests, no matter how much that doesn't make any sense!

so Starfield isn't designed in such a way where it can lock you out from any meaningful content, but it also still feels the need to let you know you picked the Bad Guys in this situation, so how does it accomplish that? passive-aggressive shaming, by way of the companions. my understanding is that all four companions - even the morally gray Andreja, who openly expresses disgust with the idea of SysDef getting to sweep this all under the rug if they win, and Barrett, who constantly seems to be making friends and pounding back brewskis with pirates - will hate your guts if you opt to side with the Crimson Fleet. no ifs, ands, or buts about it. no real opportunities for me to express the thing i'm thinking as a player, which is that SysDef is full of amoral monsters who blackmailed me into their plan to begin with, who pretend to have the high ground with their 'no killing, even to maintain cover' policies but proceed to dehumanize their opponents every step of the way.

obviously these are fake, digital people. their opinions don't really matter to me and my understanding is that it's just as easy to make them like you again as if nothing happened after they've had their single opportunity to tell you that you did a bad thing. it's not like i'm afraid of stepping on people's toes. hell, i'm not even opposed to having companions who do have strong disagreements with the player's choices - i think that makes perfect sense and adds depth to the world, because yeah, not everyone is going to agree with you all the time. the problem here is that it's everyone.

there are, to some extent, more companions available outside of Constellation's ranks, but... not really. most of them exist solely for the sake of crew-building, applying different perks to your ship. they can have maybe a single full conversation with you, but that's all they're ever going to say. they don't participate in the plot, they don't have unique things to chime in with while you're on missions. when we dip back into the main plot, it'll become even more incredibly clear that this game is fully focused on the four characters you can recruit from within Constellation. all four of them, no matter what they might imply beforehand, are all disgusted with the idea of you helping the Crimson Fleet.

remember that thing Sarah said, about how Constellation is full of risk-takers, people from all kinds of backgrounds who aren't afraid of working on the edge of the law for their common goal of exploration and discovery? remember how Vladimir, the friendly satellite operator who everyone in Constellation loves, is an ex-Crimson Fleet member himself? remember Barrett chumming it up with those pirates?

this has seemingly already become a hot button issue within the nascent Starfield fanbase, with people debating about the nature of what Sarah tells you at the start of the game, and the arguments often go in circles until they arrive back at that immediate gut feeling i got when i first heard that dialogue - you aren't 'supposed' to actually think Sarah meant that. that was the game telling you something, and trying to assign interiority to a character in a video game is a fruitless endeavor. even if Bethesda prides themselves on making immersive worlds meant to be lived in, you also have to be willing to fully disengage and know when a character's actually talking on behalf of the game designers, because It's Just A Game, Bro.

this type of game design is honestly really prevalent throughout all corners of Bethesda's titles. it makes no sense that the same person can be a traitor to SysDef and then go become a first-class UC Vanguard, and also, sure, why not, Freestar Ranger as a side gig too. Starfield allows all these contradictions to exist, and the ball is in the player's court to fill in the gaps and disengage if that type of contradiction bothers them. the game is built to accommodate the player who wants to do everything for the sake of doing it, and the only way to narrow that down and define who your character really is in this world is to keep ignoring things, rather than the game creating exciting new opportunities out of your choices.

here to perform its eighth encore as a point of comparison in this rambling diatribe against Space Game, it's Fallout: New Vegas! i think a key difference between the design of these games that isn't quite so starkly 'Starfield bad, New Vegas good' is the way these games handle factions. Starfield has a faction-agnostic main storyline - it's not a story about the politics of this world, it's a story about unraveling the mystery of the Artifacts and getting space magic and maybe learning a valuable lesson about the nature of human curiosity along the way. New Vegas is nothing but politics. the factions aren't optional chains of side quests meant to flesh out the world, they're the plot of the game, and you have extreme degrees of influence over how they play out.

in case it wasn't clear enough from how i've talked about the various factions negatively, i went for New Vegas's 'wild card' ending, in which you stumble upon Benny's plan to use the coveted platinum chip to his own ends and screw everyone over equally. to some extent, the independent route exists as a mechanical necessity - because you can kill anyone and make all the major players turn on you, you need some kind of neutral way to end the game, and having a robot who can transfer his consciousness into a new body over and over creates a quest giver the player can't permanently lock themselves out of. in my playthrough, though, i picked the independent route because it just genuinely reflected the way i felt about the conflict. the Legion are terrible, so i was willing to help the NCR deal with them, but it'd be bad for everyone involved if the NCR overextended into Mojave territory. Mr. House is just a capitalist dipshit who should be blasted at the earliest convenient opportunity, so no need to worry about him.

with the way i played New Vegas, the game's first act ended with Benny escaping from our confrontation at the Tops casino alive and winding up a prisoner of the Legion, giving me my first opportunity to come face-to-face with Caeser himself. as Caeser explains it, his fort happens to be built atop Mr. House's personal vault of Securitron drones, which ties into the true purpose of the platinum chip as an activation device. a lot of people want the Securitron army online and active, whether it's Mr. House himself or Benny trying to hijack control of the Strip. Caeser, on the other hand, obviously doesn't want the Mojave receiving any sort of reinforced protection to stop his conquest, and sends you down to destroy the facility instead.

to some extent, the way you're 'supposed' to do the independent ending is by commanding this Securitron army yourself at the battle of Hoover Dam, giving you the military backing to stop both the NCR and Legion in one fell swoop. i chose to blow the Securitrons up.

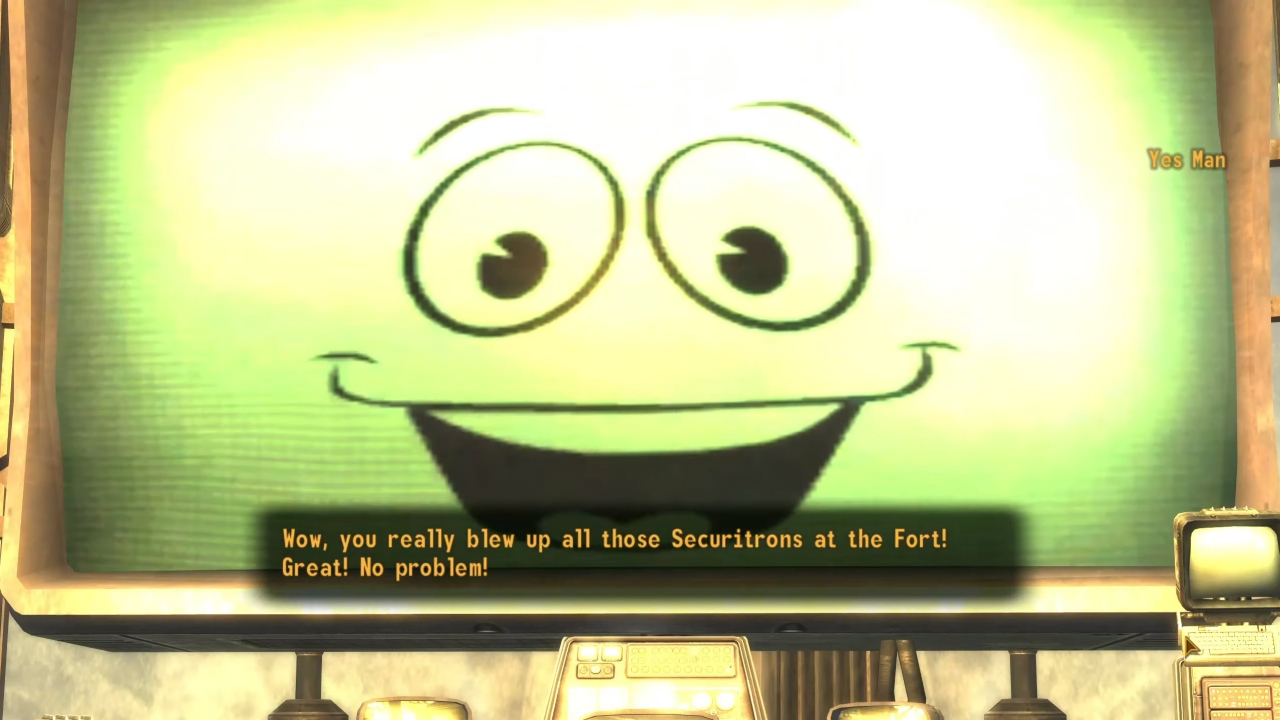

it sucked in the sense that it was what Caesar wanted, but i was willing to take that risk and find other ways to deal with the Legion. by this point in the game, i was deeply invested in the fictional politics of the Mojave, and i knew that i wanted to put the people first, people like the Followers of the Apocalypse or the Kings of Freeside. i looked at the situation and i decided that nobody would benefit from having the kind of monopoly on violence that an autonomous robot kill-squad gives you, not even myself. i wanted to de-escalate, and that was my way of doing so. this choice really did reverberate throughout the entire latter half of the game, with unique dialogue from characters noting that i was taking an absurd risk by inserting myself into this conflict without an army to back me up. for the same reasoning, i didn't help the Boomers retrieve their lost B-29 bomber, and i had to turn to the washed-up ex-Enclave soldiers for aerial support. when it came time to enter the fray at Hoover Dam, Yes Man was passive-aggressively 'thrilled' at my 'bravery' to destroy our robot army, and ultimately, i had to render the hydroelectric plant inoperable, to remove any reason for the NCR to try and stake their claim in this region. that, too, was a difficult price to pay, but given i had brought the HELIOS One solar energy station back online and distributed power throughout the Mojave, i was willing to have faith that the people of Vegas could still thrive on their own two feet.

the Fallout Wiki itself says that there is, and i quote, "no real benefit in destroying the Securitron army", no matter what path you're on. Mr. House and Yes Man both want it operational for their endgames, and the NCR and Legion both end up wanting you to kill Mr. House, which also shuts down the Securitrons. that's a big decision i made that, in a practical gameplay sense, only served to make things more difficult for myself. but it was a decision i made because i started caring a lot about the nature of this fictional conflict, and the game let me do it, and it reacted accordingly in so many ways. i felt a certain way, and the game gave me the tools to express that viewpoint and took measures to make sure it changed the world around me, even if it was counter-intuitive and senseless. often times, those reactions meant cutting me off from certain ways the game could end. there is no talking Mr. House down once you've strayed far enough from his grand vision, and the NCR eventually caught on that i was undermining their authority more and more with each big step.

you would think that in a game like Starfield, wherein the factions are entirely optional and disconnected from the main story, that Bethesda would feel comfortable drawing a line in the sand and saying "no, if you start picking sides, certain people aren't going to let you waltz in and work with them anymore". they aren't, though. this whole tangent has been to come back to that point - mainline Bethesda games are designed first and foremost for players to mine them dry. the ideological differences between the United Colonies and Freestar Collective can never truly matter, because that'd mean telling a player they can't have their cake and eat it too. if you decide to try and engage, if you want to care, the onus is on you as a player to ignore major traps of ludonarrative dissonance rather than the game itself meaningfully reacting to any decision you make.

so, i wanted to do what little i could to care. maybe it was ill-advised, because Bethesda games seem incredibly poorly equipped for that, but i wanted to put myself in my character's shoes and give a shit about what the people closest to me might think. i took the money to SysDef. it's been made clear throughout the quest that this lost treasure might make or break the long-term survival of the Crimson Fleet, but there's no way to talk SysDef down from a senseless attack on their headquarters. and so, the game sends me in to clear out the spacestation. all of Commander Ikande's moral righteousness about not killing innocent people is gone - these are pirates, they brought it on themselves by doing crime. that girl who handles the spaceships, who's in a loving relationship with Naeva? that bartender who you gave emotional closure by finding his long-gone lover's ring? don't feel too bad about gunning them down in cold blood.

as far as i can tell, there's no way to save some of these people, because they don't get the option of 'mercy by way of a prison cell'. i tried using my space magic that calms and disarms enemies, but not only would my companions gun them down anyways, but they'd pick their guns back up and storm in on me while i tried to progress further into the station. as i made my way through, i picked up a set of audio logs scattered throughout the station, depicting an interview with Jasper Kryx about the origins of the Crimson Fleet, about how the United Colonies mistreated prisoners and eventually created SysDef as a form of saving face, allowing the Navy to look heroic and successful while the new department ate the losses of being unable to clean up their own mess.