WHAT WAS THE PROBLEM WITH HALO INFINITE, AGAIN?

the year is 2018. it is E3, and Microsoft has just opened their conference with the reveal of Halo Infinite. no gameplay, no hints as to where the story might take us - more of a tone piece to convey some key aspects of the game. without coming right out and saying it, it looks like a new take on the franchise with some kind of open world, while also returning to a more classic aesthetic after 4 and 5 shifted the art style dramatically.

it's a breath of fresh air, because Halo 5: Guardians is already coming up on the three-year mark. it's the longest wait for between Halos yet - assuming some kind of pattern, the sixth game would have been expected to fall mere months after this E3 trailer. but it is 2018, and game development is only going to keep getting more different.

as i write this, we're closing in on the one-year anniversary of Halo Infinite's release. after a pandemic threw production off-course and the team fought for a full year's delay past the coveted console launch window, the game has been in our hands for quite a while now. it launched to, at least as far as i can tell, a warm critical reception. the open world isn't the deepest in the industry, but people like the moment-to-moment gameplay, because it's Halo, and it feels like some good-ass Halo. fans appreciate the multiplayer for taking a more classic, pared-down approach, merging elements from previous games to return Halo to its roots while keeping the pace up compared to the classics. before its campaign has even gotten into player's hands, Halo Infinite is crowned the winner of the Players' Voice award at Geoff Keighley's yearly solstice ritual/awards show, beating out such heavy hitters as Metroid Dread and Resident Evil Village.

if you read what people have to say about Halo Infinite today, whether on social media, gaming enthusiast spaces, or franchise-focused boards, you will see a very different picture being painted. nobody hates Halo more than Halo fans. Infinite is labeled as broken, worthless, a lost cause. it is, as people love to say, a "dead game".

so what the hell has happened over the course of the last year to make people turn around so harshly? what's the secret to unlocking the deep mysteries of Halo discourse? what brings a game from beloved to belittled, and what can that process tell us about where games as a medium stand today?

i can't necessarily promise to answer those questions. to be upfront - this post is not going to be me at my most even-handed. i am not looking at this phenomenon from the outside in. my friends have endured hearing me talk about this for the past year, and when making this very website, i knew one of its many purposes would be to contain my nuclear-grade takes about this exact issue. i am down there in the trenches of internet discourse and this article is going to be written from the perspective that what's happening to Halo Infinite actually kind of sucks, so if you're looking for me to dunk on this game, this is not the article for you. i can only hope that along the way, i will coincidentally stumble into something resembling a prognosis for these broader trends in gaming.

PART ONE: THE PROBLEM WITH HISTORIC EXPECTATIONS

'how we got here' is a messy concept. i could start in 2015, with the release of Halo 5: Guardians, a game who's own mixed reception informs many of Infinite's fundamental aspects. i could go back to 2012, when 343 Industries took the reins of the franchise with Halo 4. it wouldn't be inappropriate to jump all the way back to 2004, when Halo 2 launched and revolutionized the way games are played together over the internet. maybe our story starts somewhere outside Halo, like the 2017 release of Fortnite Battle Royale, or any number of 'games as a service' that have shaken up old industry standards of what post-launch support looks like.

pinpointing a single game as the beginning of all this seems like a bit of a futile effort though, because this isn't only a story about Halo Infinite. we have to go broader than that, across a path that intersects all of these moments in the history of online multiplayer shooters. but i also respect your time, so i'll try to be quick about it, as much as i can be.

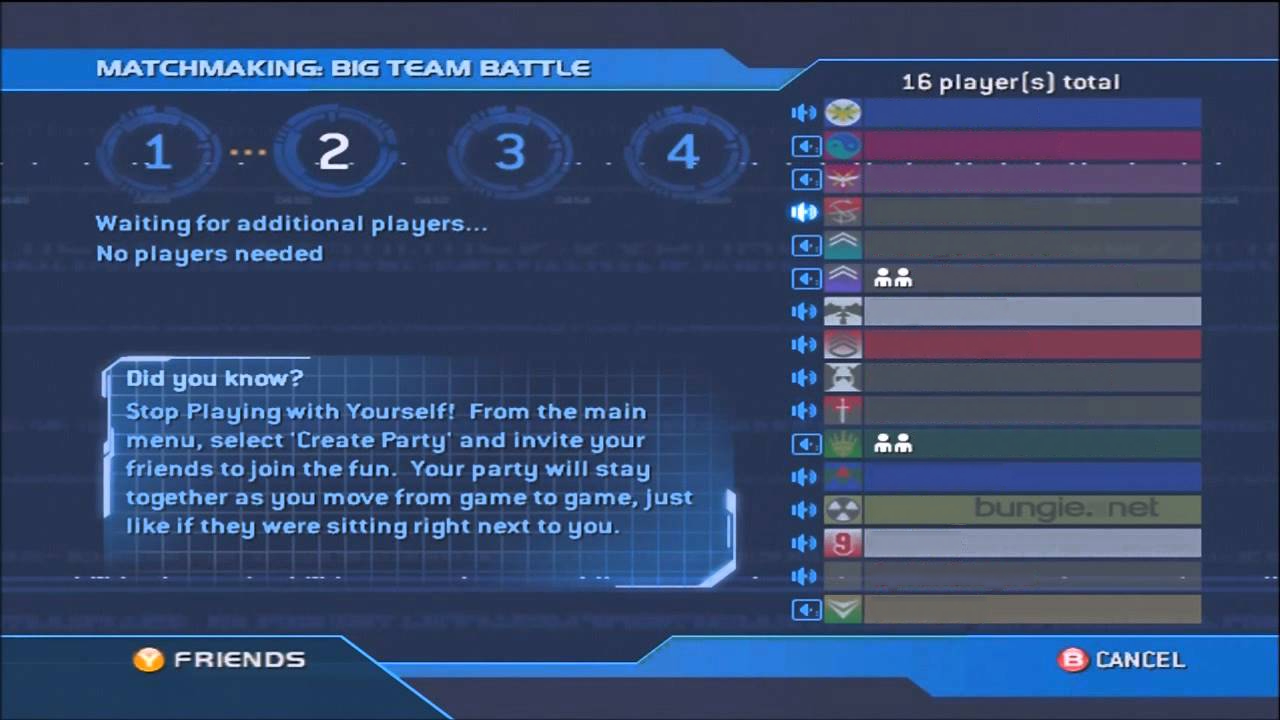

Halo is a series of sci-fi first person shooters developed under Microsoft, originated by acquired subsidiary Bungie and later handed over to a newly created internal studio, 343 Industries. it was one of the early pioneers for bringing first-person shooters to console and standardizing a control method for the genre that didn't require the keyboard and mouse setup of PC games. as the series continued, it also was a leader in championing online multiplayer through Microsoft's Xbox Live service, creating a system of 'playlists' to funnel hundreds of thousands of players together instead of relying on server browsers as its PC contemporaries did.

it is a massive understatement to say that Halo was a big deal in the 2000s. it's not a phenomenon i can even fully speak to - i must confess to being a fake gamer who, due to the unfortunate linear nature of time, was perhaps a bit young to be present for Halo's cultural zeitgeist. the imprint it left on media is well-documented, though; for millions of people, consoles were where you did your gaming, and Halo was the option for first-person shooters on a console. Halo was everywhere. it was a game, it was novels, it was a gamer-oriented soda, it was a televised competitive league, it was a burgeoning movie deal with Peter Jackson. Halo 3 was, in its time, the 'biggest entertainment debut in history', selling absolute gangbusters and pushing video games into the attention of mainstream media coverage unlike anything that had come before it.

with success, of course, comes competition. as the 2000s marched on, there were enough studios gunning for the throne that the term "Halo killer" became common marketing parlance for a myriad of first-person shooters. if any game 'won' in this regard, it would probably be the Call of Duty series, which slowly but steadily worked its way up from humble WW2 origins to eventually being the biggest competition on the market, straying from Halo's 'arena shooter' style to provide a faster, twitchier experience. perhaps its most lasting fingerprint on the genre is the ever-present progression system, constantly giving players a positive feedback loop of unlocking new content the more they play. all of the sudden, FPSes had meters to be filled and goodies to be uncovered.

with the market becoming more and more saturated with games that could genuinely contend with its popularity, Halo was in a bit of a weird spot. after wrapping up their original trilogy, Bungie decided they were ready to move on - they had said all they had to say about Halo, and it was time to go invent something new. it's a bit bizarre to think about now, but at arguably the height of their power, they successfully negotiated a separation from Microsoft, with one main caveat. there would have to be two more Halo games before they could be released from their contracts. with these terms laid out for them, Bungie got to work, and the results were odd, to say the least.

Halo 3: ODST and Halo: Reach represent the franchise at perhaps its oddest. they certainly feel like Bungie games, but both represent the studio at a time when they were ready to move on from the franchise. this exhaustion with Halo surfaces not as a lack of effort or care, but by making both games deviate heavily from the original trilogy - ODST is a single-player focused experience with a hub world and a mild coating of film noir aesthetics, while Reach effectively tries to throw the franchise back to 2001 while also embracing Call of Duty-esque design choices, such as letting players choose from different starting kits, or its overall grittier, more muted 'boots to the ground' approach to storytelling.

i feel like this bit of disclosure is going to inform a lot about the rest of this article - Halo: Reach was my introduction to the franchise. i can still remember the box sitting on the entertainment stand, and the sort of shrug of approval that i got from my family about probably being old enough to shoot some aliens at that point. it's by no means my favorite Halo game, but Reach nostalgia in the Halo fandom is a beast all its own. once reviled by the community at large, it has been rehabilitated by people who grew up on it, and its shadow will loom heavy over the rest of this story.

with Bungie taking their last bows and heading once again into independent development on a new project, the task of shepherding Halo's future fell to 343 Industries, an in-house team at Microsoft that had been quietly brewing for years since it became clear Bungie wouldn't be around to handle Halo forever. only two years after the release of Reach, they put out Halo 4, a somewhat divisive follow-up to the original trilogy. it's been praised for how far it pushed the Xbox 360 technologically and many will point to its story as the most emotional of the series, but it drew just as much ire for a number of reasons - leaning even harder into a Call of Duty-inspired multiplayer design with killstreak rewards, writing that was accused of relying too much on outside material to be understood, and an extensive reinvention of Halo's visual identity.

the pace of a new Halo game every three or so years would continue for the next installment, but before we get there, i think it's important to take stock of a few things about where Halo was at, and where video games as a whole were heading. Call of Duty had already taken a strong lead in the market, working at an even more intensive 'game per year' pace and releasing across multiple systems rather than being tied to the Xbox brand.

games like Battlefield continued to add more competition to the market, and PC gaming was on an upswing, with Valve at perhaps the peak of their power and many rallying around the catchphrase "PC master race", a phrase which, in hindsight, really makes my face shrivel up like i just bit into a lemon. it was a crowded market as the 2010s kicked off, and the way multiplayer games were designed and monetized were at a volatile crossroads where trends that seemed like immovable wisdom carved in stone could dissolve in a matter of months.

Halo 4 was the last Halo game to feature the DLC model that was generally followed as far back as Halo 2, in the form of "map packs". players would pay somewhere around 5 to 10 dollars for a handful of new arenas for multiplayer, with new packs generally coming out quarterly or so for the first year after a game's release. it was a simple model with its roots in a tradition of expansion packs being sold for PC games - you just pay a little extra, get a little extra. the problems that surfaced as the years went on were the unreliability of that purchase's value - if you wanted to see any of those new maps you paid for in online matchmaking, you had to hope the funnels grouped you together with other people who had made the same purchase, which could be anywhere for three other players to fifteen.

attempts were made to mitigate this by providing DLC-only playlists to filter out anyone who didn't own the extra content, but these often quietly fizzled out, because ultimately, people didn't want to wait longer to play on a smaller selection of maps. there were haves and have-nots, and while that might have worked in the days of Halo 2 - when Halo was practically the only game of its kind on the console market, and map packs were expected to be made free after a certain threshold of time - it wasn't sustainable as a long-term model in a changing landscape for multiplayer.

by the time the next Halo title hit the market, the way games were being monetized was changing. if you had transactions in your game, you wanted them to be small, like some kind of… micro-scale exchange of money. if only we had a term for that.

there was a time in gaming when actual analysts who actually get paid with very real money to analyze the industry earnestly thought that mobile gaming on phones would decimate the console market. consoles cost hundreds and the standard price for a full-fledged game was hovering around $60, so how do you compete with a computer everyone carries in their pocket that has games for only 99 cents?

you adopt their strategies. you make the barrier for entry lower, and the transactions smaller. it was a time of growing pains for games, especially competitive multiplayer games such as Halo, where developers constantly had to walk the line of providing value in small purchases without stumbling into the dreaded territory of "pay-to-win" by offering anything that actually made players perform measurably better at the game.

in 2015, Halo 5: Guardians released, and before we delve into how its multiplayer embraced the trends of the time, we need to unpack where it sits within the franchise's history on a different level. it was a tumultuous time for the series - the year before, the Master Chief Collection launched with debilitating, game-breaking bugs, and it was still in a state of very limited functionality. 343 Industries was seeking to push Halo as a brand further than ever before, promising a television series executive produced by Steven Spielberg and launching their own 'Halo Channel' app for the Xbox One in anticipation of a new multi-media vision for the franchise's stories. Halo 5's story was a hard swerve from what Halo 4 had provided, ditching the overarching didact plot they had invested a trilogy of novels into and instead focusing on the shocking twist of reviving Cortana as a villain spearheading an AI uprising. if fans couldn't embrace Halo 4's direction, they would simply wipe the slate clean and go somewhere Halo had never gone before.

on the multiplayer side, Halo 5 was fundamentally split down the middle into two halves, which shared all the same basic mechanics but strived for two very different goals. fans had loudly protested the loadouts and killstreaks of Halo 4, so 343 Industries sought to bring the series back to its arena roots with the aptly-named Arena modes. Halo 2 was a pioneering game for 'esports', but later installments never quite caught the competitive scene's attention in the same way, so Halo 5 was carefully crafted to zero in on this aspect of the series. where it deviated from the classics was in its enhanced mobility, with all players capable of running, climbing, hovering, and jetting around the map. many have argued this is a case of Halo looking to its competitors for inspiration, and it's hard to deny that in the mid-2010s, this kind of heightened, 'split-second decision' mobility was very in vogue.

the other half of the multiplayer suite came in the form of Warzone, a mode meant to expand on the large-scale combat of Halo by combining PVP elements with a variety of active objectives and an AI presence on the field. unlike in previous Halo games, the 'small' and 'big' multiplayer experiences couldn't really overlap; Warzone maps were for Warzone, Arena maps were for Arena. it was in this side of the experience that Halo 5 embraced the next evolution of microtransactions - the loot box.

loot boxes are a fascinating artifact of mid-2010s game design in terms of how omnipresent they felt in multiplayer games and how quickly they seemed to all but vanish from all games. i can't necessarily speak to every single design choice that lead to them, but the fundamental principle seems clear - if you're trying to make the transactions as small as possible but still want repeat buyers, and if the thing you're selling is trying to avoid making players objectively better at the game, why not leave the purchase up to chance and pull from a random pool of items?

(gambling. the reason you don't do that is because it's gambling.)

Halo 5's loot boxes, known as REQ Packs, weren't the most egregious on the market, but they certainly weren't great, either. REQ Packs contained two broad categories of items - purely cosmetic content like new armor and weapon skins for your Spartan, and single-use cards that were deployed in Warzone mode. rather than scavenging for your power weapons as in traditional Halo multiplayer, Warzone had players draw from a limited cache they owned, regulated by an in-game scoring system that required you to play well to earn the ability to call in stronger equipment. in a very technical sense, it's not pay-to-win, because you still have to 'earn' the right to call in your power weapons, and if you die, anyone is free to pick them up and continue using them, but it's certainly tip-toeing the line.

as with most loot boxes of its time, one way the game tried to pre-emptively cut off complaints of paying to win was by making the packs earnable with in-game currency. i would know this very well - i put hundreds of hours into Halo 5 and unlocked almost every bit of armor the game had to offer, only ever paying real money in cases where items weren't being offered for points. hypothetically, it is a thing anyone could do if they're willing to play a lot of Halo 5. on a personal level, i would never recommend anyone try to do it - i was at a point in my life where i had the capability to play basically as much Halo as i wanted and it still took me a good two or three years to accomplish, and i would hardly call it 'worth it' nowadays.

reactions to Halo 5: Guardians as a whole are a bit tricky to gauge, in the sense that i think a lot of players do not like it, and those that do almost take a sort of begrudging stance about it - a sort of "you couldn't understand Halo 5 because you weren't in the trenches with me grinding to rank 152" approach, almost? it also doesn't help that in the wake of Infinite, plenty of people are willing to double back and try to defend 5 as somehow being better despite how much of it they detested back when it was the headliner of the franchise.

people certainly didn't enjoy the story any more than Halo 4's, although the reasons why often differ from person to person, with a common complaint being a lack of focus on Master Chief in favor of a new secondary protagonist, Jameson Locke. Locke is definitely not the most engaging character ever, and his introduction through live-action miniseries Halo: Nightfall left basically no impression, but i get the sense most people just have a weird attachment to their specific vision of Master Chief and felt some level of offense that he was being sidelined for this game.

it also feels like it might be irresponsible of me to not point out that Jameson Locke also happens to be black - most discourse about him doesn't read as overtly racist, but especially when talking about capital-G Gamers, it is unavoidable that certain people were definitely critiquing him from a prejudiced angle and that perhaps fed into a broader distaste for the character.

in painting a picture of how we got to Halo Infinite, it's also important to talk about two concepts that sculpted the narrative around Halo 5 - "missing features'' and "games as a service". despite certain elements being designed with cooperative play in mind, Halo 5 was the first game in the series to exclude local splitscreen co-op. other features, such as the series' Forge map editor mode and Big Team Battle multiplayer, came after launch in the form of free monthly updates. this was the upside of the microtransaction model; if you push enough sales for small, unimportant things, then you have the money to provide larger content updates like new maps and features for free, eliminating the issue of splitting your playerbase. overall, though, there was a pervasive sense in the fandom that Halo 5 was missing some substantial features and that these were something to be outraged about.

our deep dive into the history of multiplayer games and how they influenced Halo Infinite's design doesn't just stop with its immediate predecessor in the Halo franchise, though. within a few short years of Halo 5's launch, many of the trends it had ridden the coattails of had already vanished from the landscape, making it feel like a preserved fossil even only seven years after its release. enhanced mobility, while never quite disappearing, didn't stick around as a genre hallmark in other franchises, and after games like Star Wars Battlefront II pushed loot boxes to their absolute limits, the looming threat of government intervention led to the industry largely washing their hands of the whole idea.

as platforms like Twitch skyrocketed in popularity and changed the ways playerbases interact with games as a medium, the next big trends that overtook multiplayer shooters seem almost tailor-made to produce games that are incredibly engagement-driven. for a moment, it seemed like class-based 'hero shooters' like Overwatch would be the new standard of choice, but out of nowhere, PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds set the stage for the 'battle royale' genre, flipping traditional competitive multiplayer on its head into a slow burn survival challenge, but without a doubt, the most influential multiplayer game of the late 2010s is the game that came in and ate PUBG's lunch, Fortnite Battle Royale.

i remember installing Fortnite briefly when its battle royale mode was first blowing up and wondering what all the fuss was. in hindsight, all the ingredients were pretty shockingly obvious. PUBG cost money, was exclusive to PCs for a long time, and had its roots in mods for games like ARMA, focusing on a very grounded tone with real world finicky gun physics. Fortnite took that same feedback loop of striving for a win against 99 other players, used much game-ier physics, and was completely free. of course people gravitated towards it.

while the 'battle royale' genre itself became oversaturated over the following months, perhaps an even broader impact Fortnite brought to the table was the idea of the 'battle pass'. it's a concept that originated with MOBAs like Dota 2 years beforehand, but Fortnite's explosive popularity at a moment when the games industry needed a quick, easy replacement for loot boxes effectively locked battle passes in as an overnight must-have for any new multiplayer release.

battle passes combine old-school meter filling with new-school monetization - players progress by playing the game more and more, with a set track of cosmetic rewards, generally split into a free tier and a paid 'premium' tier with more enticing prizes. the paid tier also usually includes enough currency to pay for itself, with the caveat that these passes are tied to limited seasons and disappear once they're over. in this sense, the developers don't have to worry about you earning your future passes for free - they've got you hooked, because you have to be dedicated to playing their game, and maybe only their game, to pull that off. for anyone who doesn't earn back their money in time, tough luck.

so that leaves us at some point in the late 2010s, going into the 2020s. over the course of the decade, the standards for online multiplayer have shifted dramatically. games that were once supplanting Halo with their innovative new systems have now come full circle, trying to adopt the innovations of their newer successors to get a slice of the pie. Fortnite is putting out new content at a blistering rate, practically reinventing itself every few weeks to meet player demand, with an increasing focus on high-profile brand tie-ins. the hardware people play on is stronger than ever, with players demanding higher fidelity than ever to match, yet almost every major player in the multiplayer space has to offer itself up for free just to stand a chance of building a following.

i don't think i've actually managed to make that a short story. anyways, how is Halo doing around this time?

PART TWO: THE PROBLEM WITH BLAM! AND SLIPSPACE

as support was winding down for Halo 5: Guardians, all eyes were on 343 Industries to see where the franchise would go next. there was a general sense in the fandom that this had to be the time they got it right - players both casual and professional were advocating for a return to the fundamentals of the Bungie games, whether that was in terms of broad mechanics or minute details.

somehow, as a result of this type of thinking, one of the very first things we heard about a sixth Halo game was that the Spartans would once again have black undersuits for their armor. as someone who was in the fandom at the time, i can assure you, this was an actual thing that people, including myself, complained about, and even at their most tight-lipped, 343 Industries wanted us all to hear that this very specific feedback had been heard.

other than this definitely absolutely critical bit of information, things were quiet. many of the minds behind Halo 5, both in terms of its story and its gameplay, quietly left the studio in the intervening years. interviews gave the impression that 343's main takeaway from critiques of Halo 5's story was "these games need to be all about Master Chief", with little said about things like Cortana's death being undone for the sake of a twist. one early promise from studio head Bonnie Ross was that every Halo going forward would include local split-screen support, in response to backlash against its absence.

now that Infinite has been out in the wild and gaming journalists have sought to dissect the nature of its development, we know a bit more about what was going on behind the curtain during this time. the team was shuffling around into new positions post-Halo 5, and new ideas were being tried out. one bit of information that has become increasingly notorious in the fandom is that some amount of time was spent prototyping a sixth Halo game in the style of Overwatch, with different preset classes.

both the developers at 343 and the very journalists who unearthed this information have emphasized that this type of experimentation is extremely normal for any game to go through, but people seem very eager to wield this information as some kind of sign of incompetence - how dare they even try, they wasted time on this and that must be why I don't like the game, etc.

another point of contention in the fandom is the development of Halo Infinite's Slipspace Engine. all Halo games, dating all the way back to 2001, have run on the same fundamental bones that Bungie developed, known as the Blam! Engine. not only are proprietary engines much harder to program for than off-the-shelf solutions like Unreal, but this was one that had accumulated almost twenty years of odds and ends across multiple studios and multiple games that came in infamously hot. one of the first things revealed in the wake of the E3 2018 trailer was that Halo Infinite would be moved to a new proprietary engine, known as Slipspace.

Slipspace, at its core, is not an entirely new engine. it still contains several elements of the Blam! Engine. this, again, is often pointed out as perhaps some kind of waste of time or outright false advertising from 343 Industries. my understanding, from reading about these engines and hearing takes from people who do work in game development, is that this is all incredibly normal. engines like Source and Unreal still contain very old components because making game engines is an iterative process and most studios work under the assumption that upending decades-old code to replace it is only going to create even more issues. i cannot claim to have personal expertise on the matter, so i could be entirely off-base, but most of the people complaining about this type of thing in the fandom are equally inexperienced with game development, so there's that.

all my attempts to clarify game development processes aside, it does seem like Halo Infinite had a particularly tough production process. high-level employees cycled in and out of the company and it seems to have taken some time for the team to pin down what the direction of the project would be. all of these issues were only magnified by Microsoft's hiring policies, focusing on hiring contract workers but also putting a limit on how long they can stick around.

this meant a developer might work 18 months on the game, have no choice but to leave, and then be replaced by someone who needs to spend some of their own 18 month contract being caught up to speed. this whole process seems highly inefficient and almost assuredly isn't great for the people actually making the game. when i bring all this up, it isn't to excuse poor hiring policies, but to elaborate on the realities of how this game was developed, for better and in this case for worse.

on the subject of months and years, a third correction i feel like addressing is the amount of time between games. people often throw around "6 years of development" when talking about Halo Infinite's shortcomings, and the answer is a lot more complicated than some flat amount of time a game is in production. work on the Slipspace engine seems to have started around 2016, and pre-production was certainly in motion, but games do not just start getting made the second the previous one is out, especially nowadays when you see games such as Halo 5: Guardians receiving extended support through updates. 'the sixth Halo game' is certainly an idea that was being kicked around for six years, but that is not the same as what people like to imply, which is that Halo Infinite was in full-blown production for that entire time.

it's hard to pinpoint exact dates on when the project we would recognize as Halo Infinite actually started to come together, but by some time around 2018, it seems like the broad goals were in place - a return to classic-style Halo gameplay with an expanded sandbox and an open world campaign. it was a massive undertaking, and to compound things even further, it was being positioned as the lynchpin for a generational shift, releasing across the Xbox One, its beefed up Series S/X older brother, and PC. even as the vision of what Infinite is came into focus, it seems like development was a struggle as separate teams brainstormed what 'open world Halo' would mean and tried to cover all their bases.

during this phase of development, things stayed somewhat suspiciously quiet, with generally yearly updates around E3 season. just as 2018 had brought us the first showcase of the Slipspace engine, 2019 showed off the introductory cutscene for the game, establishing the tone of the story, with the mysterious hook that Master Chief had been drifting unconsciously through space after the events of Halo 5 and woke up to a world where the UNSC had lost a major war in the meantime. occasional details would trickle out between these showcases, but for the most part, Halo Infinite was being kept close to the chest - perhaps with the thinking that it would be best suited as a secret weapon for the launch of Microsoft's next-gen consoles, or perhaps due to troubles behind the scenes.

the floodgates truly open with the not-quite-E3 digital showcase in 2020, with a 8-minute demonstration of real gameplay footage. i remember watching this and being really excited - the idea of an open world Halo game was a bit scary in terms of my distaste for most modern AAA open worlds, but the combat encounters looked fun, with so many clever expansions to the traditional Halo combat loop, like being able to pick up explosive coils as makeshift weapons or the addition of a grappling hook. it has been my long-standing opinion that all video games are better with a grappling hook, and now, arguably my favorite game of all time had one. it was great! and the art style was clearly skewing closer to the classics with less overbearing lighting effects and detail, focused instead on instantly readable silhouettes and a bright, bold color palette.

so, anyways, people hated this fucking demo.

hated might be a strong word - the gameplay elements were all relatively well-received, perhaps with some caution from old-school fans but with an overall sense of optimism when discussing how the game might play. the issue, then, was that most people had very little interest in talking about the gameplay. the primary feedback from this demo was dissatisfaction with the graphical quality of Infinite.

my personal opinion is that the backlash to this demo was vastly overblown due to its place in the broader context of a generational shift in consoles. as much as it is easy to feel like perhaps discourse around video games has risen above petty shots back and forth about which of these two $500 computer boxes is better (despite them being more and more similar internally as the years go by), the console wars are still very alive, and Halo Infinite was seen as some kind of colossal misstep in Xbox's marketing for its next-generation hardware.

to very quickly go over my points against these arguments; Halo Infinite was being built for a range of hardware dating back as far as 2013. graphical polish and optimization, to my understanding, often come pretty late into development once you have your gameplay fundamentals locked down. and, perhaps most frustratingly, the game's art style was everything people had been asking 343 to return to for years. i'm not going to sit here and tell you the demo looked fantastic or anything, it definitely represents a product that isn't in a finished state, but in my opinion, having a cohesive art style is astronomically more important than the resolution it's being rendered at or whatever.

the demonstration was definitely representative of a work-in-progress, but the overwhelming narrative around the demonstration was that it was some kind of disaster. as people dissected the footage, a particular frame of a Brute people labeled as Craig became an emblem of people's concerns with the game's graphical prowess.

we're not going to talk about Craig yet, but i have a lot to say about Craig. keep Craig in the back of your head.

in the weeks after the campaign demo, two major pieces of news dropped that would continue to stoke discourse around the game for better and for worse. the first came about a week after the presentation - after listings were unintentionally put up early, Microsoft ended up rolling with the news and officially confirmed that Halo Infinite's multiplayer would be free to play. to some extent, this came as a surprise, but given the state of the market, where almost every major competitor is also offering free access to their games, it shouldn't have been too shocking that this would end up happening one way or another. some people were certainly excited about the new visibility this could provide for the franchise, but others were already mentally prepared for the worst case scenarios of how the game might be monetized as a result.

the other shoe dropped a few weeks later that Halo Infinite would be pushed into 2021, missing the launch window of the new Xbox. it definitely felt like the delay was in response to the overblown concern over the game's graphics, but as we can now see a little more clearly, there were other issues behind the scenes that definitely made this delay worthwhile. around the same time, it also became clear that franchise veteran Joseph Staten, writer of the original Halo trilogy, would be joining Infinite as its new creative lead. unfortunate circumstances, but overall, choices that all probably led to the game itself being better.

news once again started coming out on a regular basis late into 2020 as we started getting monthly blog posts from 343 Industries, consisting of internal interviews with various departments of the studio. i would say the most notable of these in terms of community reaction was in December, with an update from the art team talking about multiplayer cosmetics, namely the newly introduced 'armor coating' system.

for those unfamiliar - traditionally, in every Halo game up until Infinite, the most consistent, basic form of cosmetic customization for multiplayer was choosing from a limited pool of colors for your character's armor. Halo Infinite instead uses pre-made 'coatings', created by the developer and mapping different colors onto your armor in different ways. this decision is said to have come out of a desire to have more expression possible, by playing with things like different textures and patterns. another benefit noted was that in previous Halo games, your colors would only be visible in free-for-all modes whereas the much more popular team-based modes would override you into a solid color 'uniform'; coatings would be visible in all modes, with the addition of a colorful outline over players to denote between allies and enemies.

the armor coating debate has been raging non-stop since this information was made public, and it's one i have some mixed feelings about. it's easy to read certain criticisms of it as reductive or bad faith, talking about how they only did this to be able to 'sell you the color blue' or whatever, but unfortunately, coatings have sometimes been overpriced in the game's store. one hill i am willing to die on, though, is that coatings are not, in isolation, a completely bad idea - plenty of people will bemoan how they can't use 'their colors' anymore, but ultimately, i'm willing to trust actual professional artists with providing a satisfying range of palettes.

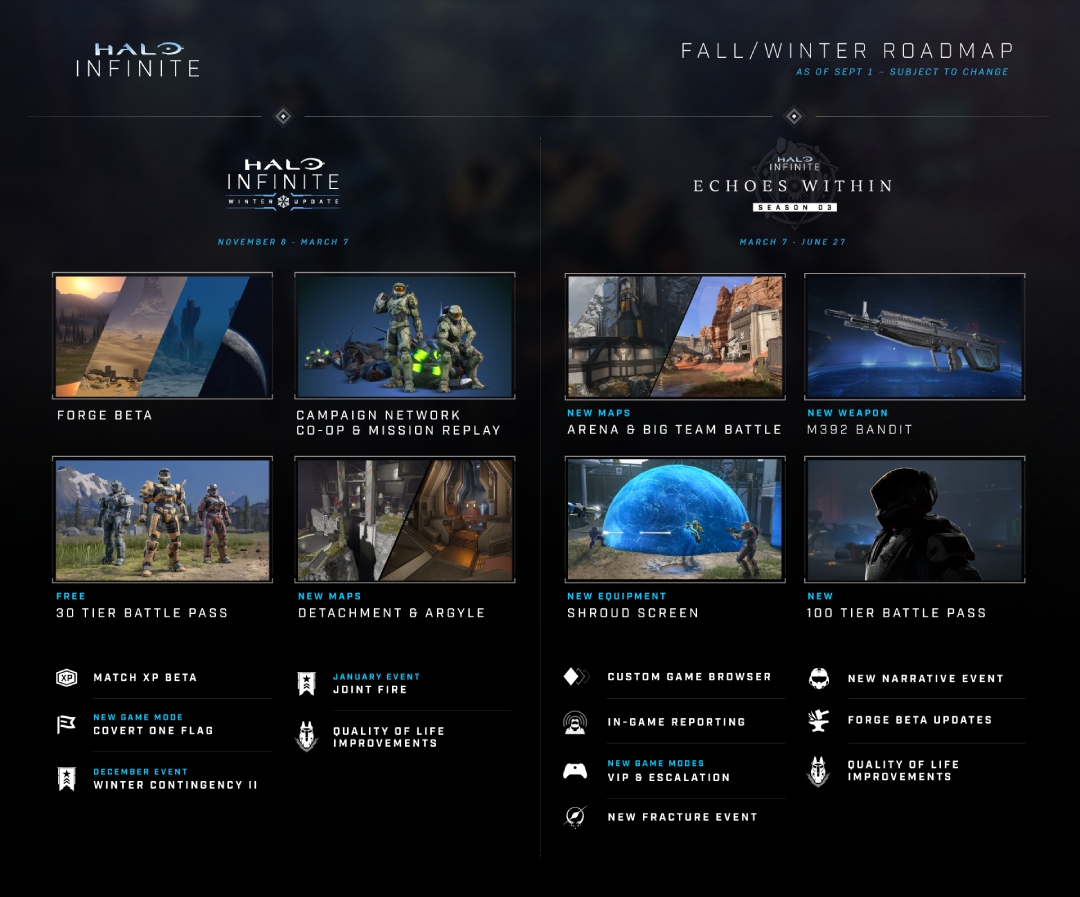

things continued on like this for a while, with a bit of news to chew on every month or so, with occasional merch leaks getting the fandom riled up wondering about the context they might provide for the upcoming game. things really got into a full swing again during E3 2021 as we received a new trailer for campaign, giving us more context for the game's plot, and an extensive look at multiplayer, revealing some of the systems the game would be built around, such as including bots and a training mode for the first time in Halo's history, or, as many had predicted, the inclusion of a battle pass.

the response to the multiplayer reveal was rather positive, from what i can remember - the team had a strong focus on translating classic Halo to a modern context, showcased new pieces of the sandbox such as the Grappleshot and Repulsor, and for a lot of people, the most relieving information to hear was the way they would be handling their battle pass system. items would be single-source (meaning that nothing in the battle pass could be bought through a storefront, or vice versa) and the seasons would never expire, allowing players to complete their passes at their own pace or double back to old seasons they had missed. it seemed like the team had found answers everyone could be satisfied with, and the mood in the fandom seemed to be a sort of held-breath optimism that perhaps 343 Industries would nail the landing on the game.

it wouldn't take long after E3 2021 for fans to get their very first hands-on experience with the game, as 343 Industries used their established Insider program to begin inviting players to a technical test for the game's multiplayer, the first of which came at the end of July. reactions overall skewed positively - there were certainly those who nitpicked some of the finer details, but the community seemed happy with how the game played and 343 was quick to put out reports about some of the larger-scale feedback they had gotten. in September, the tests were opened to an even wider audience (including myself) to stress-test the game's dedicated servers and introduce new modes, and the excitement was building as more and more people got their hands on what many would argue to be the best-feeling Halo in over a decade.

between these two major tests, though, came another tough pill for the Halo fandom to swallow - campaign co-op and Forge would be pushed back into 2022, missing the game's 2021 launch window. reactions to this were incredibly heated, with many swearing the game off, insisting they only ever play Halo in a co-operative context. it might just be my own personal history with the series speaking, but i found it surprising the amount of people (or perhaps just the volume they were producing) who are so deeply committed to only experiencing the game through this lens.

it is with the feature delay on co-op and Forge that we begin to see one of the most pervasive narratives around Halo Infinite taking shape - "all these other games had this, so why can't Infinite?". this argument, this 'they don't make 'em like they used to' rhetoric, is sort of the core of why i feel strongly enough to write this thesis. it is, in my opinion, a shallow misunderstanding of how games are made that has poisoned the well on discourse about games like Halo Infinite and made one of my hobbies actively exhausting to try and engage with in a communal sense.

it's hard to recount the wait until December 8th from any perspective but my own; i mostly remember the excitement coming off of the multiplayer test, but i'm certain that reactions came with a much finer grain of salt than mine in some cases, with the feature delay being a sore point for fans and the looming worry of things like armor coatings making some people staunchly prepared to start pushing back before the game was in anyone's hands. soon though, an insider with utmost access to the inner workings of 343 Industries gave the Halo community a collective rush of excitement. enter Pringles.

okay, Pringles was just a part of the puzzle, but the Pringles countdown was a very real part of the build-up in early November. leakers and insiders had heard through the grapevine that Halo Infinite's multiplayer component would be launching a full month ahead of time on November 15th, marking the 20th anniversary of the original game's release, and as fans volleyed back and forth over the credibility of these claims, Pringles just so happened to put up a countdown on their site - ticking down to November 15th. later evidence shows this was entirely a coincidence and that the marketing team at Pringles had no idea what was going on, but for many people, this was what sealed the deal, the coup de grace. any 'professional journalist with reliable inside sources' could lie on the internet, but Pringles would never.

(Pringles kind of didn't know what was going on, and therefore their actual capacity for dishonesty is still an unknown factor, but it's the thought that counts here, folks.)

November 15th arrived with an anniversary stream to talk about the history of Halo, and just as predicted, it came with the confirmation that Halo Infinite's free multiplayer component would be going into an 'open beta' state later that day. this beta label was, admittedly, being used much in the same way it's tossed around for other early releases - a smokescreen for any potential first day jitters, but a fully finalized product in almost every way, just meant to be put into player's hands earlier than expected. we'll revisit how different people interpreted that label soon, but for now, it's time to finally start talking about the video game this essay is about.

PART THREE: THE PROBLEM WITH LAUNCHING

so, Halo Infinite's multiplayer component was out and in people's hands, completely free. i'll go over the state in which it launched and how people reacted to it momentarily, but it feels important to establish a baseline of what i personally think about the game.

it's really good. my experience with Halo is an odd one, in that i can't say i was very present for the classic arena-style shooters Infinite is attempting to call back towards, but through a combination of general osmosis and being able to play those original games through the Master Chief Collection, i've gained a lot of respect and appreciation for that style of game design, and i can recognize that arguably as far back as Reach, that game design had been tweaked and gotten further away from what Halo was in the past. i would hesitate to call games like Halo 4 or 5 strictly bad - they absolutely still have their strengths and don't feel poorly thought out, 5 especially - but they were definitely caught between trying something different and being beholden to Halo's roots.

Halo Infinite feels like a much more finely crafted blend of modern elements with classic arena shooter gameplay. movement is faster and snappier than the floaty, weighty feel of games like Halo 3, but without becoming overwhelming to keep up with. the weapon sandbox is fantastically tuned with a focus on making sure no weapon feels redundant in the lineup - a few might see a little less usage in my hands, but everything feels like it was built with a reason to exist, a role to fill that makes it worth considering as an option when scavenging for your loadout. Infinite also brings back the equipment slot from Halo 3, a move which i personally adore. the lineup of equipment has been reinvented from the ground up with additions like a grappling hook or repulsor, but the idea of offering up unique abilities like this as map pick-ups that are meant to be fought over just like power weapons feels like the perfect way to spice up Halo's combat while staying truer to what makes that combat loop so satisfying and engaging.

personal takes on gameplay aside, the launch of Infinite's multiplayer went fairly standard - there were caveats, namely the announcement that the game's first season would last six months so that Season 2 could be developed at a healthy pace, but the game was functioning more-or-less as intended from a gameplay perspective. technical issues are a broader issue that we'll have to unpack later, but overall, the game was in steady shape, especially compared to contemporary multiplayer launches of late 2021.

so, if the game was pretty fun and worked as intended, why was the Halo subreddit put on lockdown mere days before campaign launched in December?

there were a variety of gripes to be had with Infinite's state at launch, with probably the most prominent from a directly gameplay-based perspective being the lack of multiplayer playlists, with only a handful of modes and no dedicated playlist for people who only wanted to play Halo's basic Slayer mode. it's interesting the ways in which these two complaints almost seem to pull in opposite directions - you have loud demands for more modes, but also a vast majority of players who only wish to engage with a handful of core modes, and a well-documented history of Halo's more objective-based modes not being given the same attention when spun off into their own playlists. obviously, the Halo community is not a monolith, and i don't think that the overlap between "more modes" and "Slayer-only" people is a perfectly overlapped Venn diagram, but it's representative of a fact Halo Infinite butts up against a lot - Halo means a lot of things to a lot of people and they all care about those very specific slices of the experience a lot.

all this critique over playlist selection was not the primary driving factor behind the toxicity that led to r/halo being shut down temporarily, though. the main point of contention for fans of Halo was cosmetics, and how those cosmetics were made available to players.

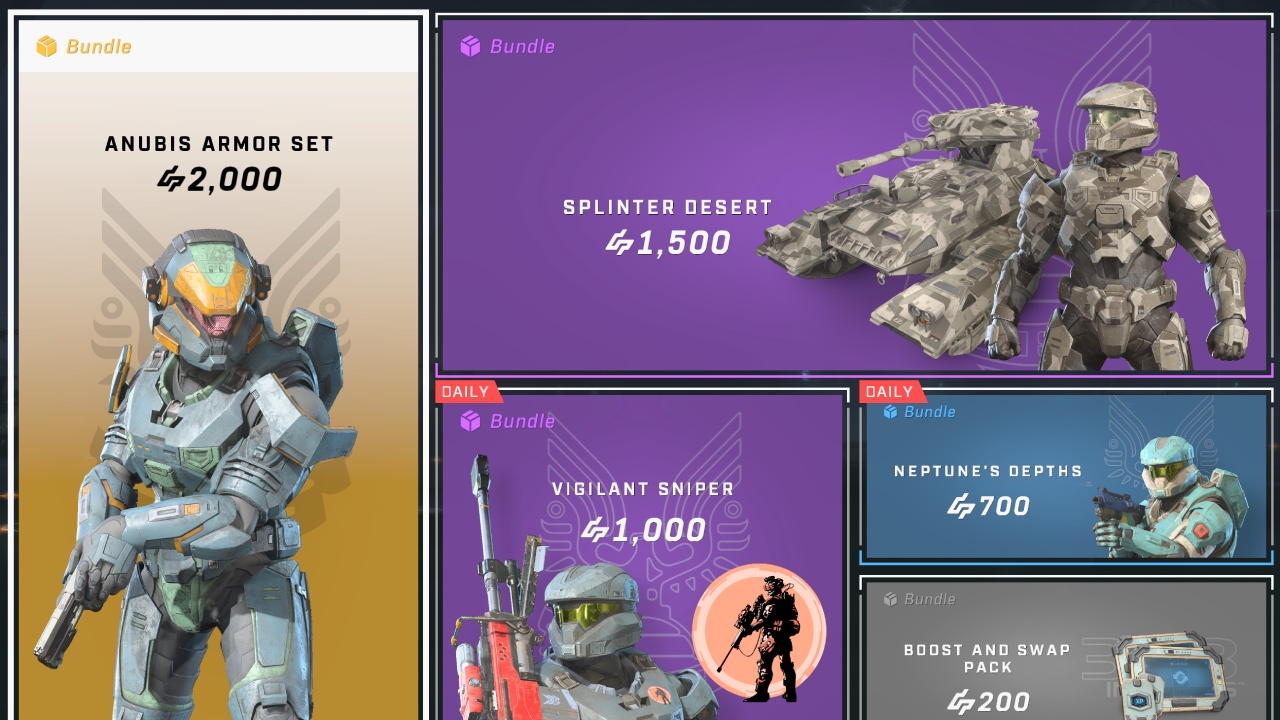

Halo Infinite provides a variety of different ways for players to obtain new cosmetic items - there is a 100-tier battle pass per season, which contains both free rewards and a $10 premium track. there are weekly 'capstone' challenges, unlocked by completing smaller challenges and awarding one unique new cosmetic per week. and then, there's the store, which, at launch, had two weekly slots and two daily slots. the first season of the game was dubbed Heroes of Reach, and focused on cosmetics based on the fan-beloved armor from Halo: Reach, offering up the Mark V [B] as a separate 'armor core' while also building out a lineup of new designs for this game's default armor, the Mark VII. there are also generally smaller events rotating in and out every few weeks, with one per season being a recurring 'Fractures' event focusing on a sort of alternate universe approach to the Halo aesthetic, with Season 1 having the samurai-themed Tenrai event as its Fracture.

there's a lot to unpack about the way cosmetics work in Halo Infinite. the armor coating system was still as unpopular as ever, especially now that the shop was fully open and indeed sold additional palettes for Spartans, and armor cores similarly compounded the problem. armor cores effectively split customization items across different suits of armor - a Mark VII suit can't be equipped with any of your Mark V [B] items, for example. this applies across all items, including the coatings themselves, which, at launch, left customization feeling a bit fragmented between different sets of gear.

the battle pass was met with a lot of very interesting reactions. the free track focused on rewards for the Mark VII armor core, while the paid track covered most of Reach's armor designs, prioritizing items that were used by the game's protagonists, NOBLE Team. common complaints at launch were a lack of cosmetic rewards on the free side of the battle pass - with many accusations that XP boosts and challenge swaps were being used as 'padding' - and the pace of progression. XP was doled out specifically through the completion of challenges, and leveling up could certainly take a bit of time.

where the complaints about pacing interest me the most might be in comparison to the game that this first season seems to be tapping into as its potent nostalgia bait. Halo: Reach's system of progress was an intense grind - to be fair, you received points across a much wider range of activities than in Infinite, but leveling up was on an exponential curve where it could take months, if not years of play to attain high levels, and those levels didn't guarantee you a reward. leveling up would unlock new options in the game's catalog for you to spend your points on, but once those points were spent, they were gone.

with Reach, i distinctly remember playing nothing but the most optimal points-earners like Grifball for weeks on end just to have the opportunity to pick which of two options i would buy for my Spartan first, and then it would be another month at best before i could double back and get the other one. Halo Infinite's unlocks might have been slower than some people would want them to be, but they were still leagues more attainable than Reach's, and as the developers had continued to emphasize at every step in multiplayer's promotion, Infinite's battle passes don't expire like in other games - there was no need to hurry beyond a player's personal desire to have higher level items.

the third angle of this criticism, and the one i can relate hardest to, was the in-game store. $10 for a 100-level pass that never expired seemed like a fair price and i was okay with putting that money forward, especially for a free game. the issue, then, was the pricing on the store. right off the bat, the game was offering bundles going for $20, and these bundles contained effectively one 'set' of armor, usually for the Mark VII core. these were, bluntly speaking, bad deals. if there was anything to point at and label as 'being done wrong' at launch, i would say this was it.

so you have on your hands a game that is widely agreed to play very well, with people's main critiques being a desire for more modes and a dissatisfaction with the state of cosmetic customization. campaign is just about to come out and people are excited to see what's being brought to the table. more than a few had taken this direct quote -

Importantly, with the Season 1 extension, we aren't just stretching-out our original Season 1 plan. Indeed, we took this opportunity to add additional events, customization items and other content to Season 1 to make it an even richer experience from start to finish.

- Joseph Staten, from 'WELCOME TO THE HALO INFINITE MP BETA'

- to mean that December 8th would come and the game would suddenly receive a major update with multiple maps, despite no specific details ever pointing towards any updates that large coming that quickly. as i mentioned at the top of the essay, voting for the "Players' Voice" award at the yearly Game Awards was well underway at this point and Halo Infinite was blazing a trail towards a decisive win in a competitive field.

but then, on the other side of the coin, the Halo subreddit is put on temporary lockdown on December 5th, mere days away from the game's full launch. people hate armor cores and coatings and the way it fragments the customization experience. people hate the store and its prices. people hate how slowly they're gaining XP, and when tensions run high in debates, you see a sentiment starting to grow amongst those who feel this way - "if i'm not leveling up, why should i play Halo Infinite?"

this is essentially the guiding lodestar for where all Halo discourse in the year afterwards begins pointing. those who are angry are incredibly eager to take 343 Industries to task for the grievance of not progressing fast enough, and those who are optimistic about the game still tend to do so through a lens of what they assume will be coming soon rather than the game they have in front of them now. it doesn't take long for the quality of gameplay to take a backseat to these issues around player expression and progression.

even campaign's launch is caught up in these conflicts - the game offers up cosmetic unlocks via armor lockers scattered throughout its open world, and people got caught up in semantic debates over feeling misled that these cosmetics were paintjobs rather than full kits of armor, to the point of trying to weasel more information out of reviewers with early copies and getting mixed messages in return. the fixation on cosmetics became pervasive to the point of becoming the biggest talking point around Halo Infinite's launch, above all else.

it has been said on this site before and it will be said again - i like character customization. a lot. anyone who has watched me play a video game where i can make a guy can vouch for this. i care a lot about creating an avatar for myself, choosing an aesthetic i like, and in the case of Halo, i have a consistent 'vibe' i like to go for, as if my Spartan has been along for the ride in all of these games and each new entry is just another opportunity to build on those aesthetics. much like many fans will loudly tell you, i have 'my colors' that i wear in Halo. i'm saying all this to establish that i'm not trying to swing hard against customization in games - i am not someone who would derogatorily call picking out armor 'dress-up'. i love engaging with these types of systems, even in first-person games like Halo where you can argue you'll rarely get a good glimpse of that work you've put in.

all of that being said - none of that could ever make me hate a video game. what matters to me about a video game is if it is fun or not, and Halo Infinite, to me, is fun. i would love to have more armor and more options for how to put it together and super-granular control over a bunch of details. if that's not there, that's okay. the game is fun and i play it for the sake of it being fun.

anyways.

campaign launched, and the impression it left on fans was somewhat mixed. many critiqued the story, claiming that all of the interesting things happened before the game starts, or complaining that Halo 5's story was effectively being overwritten, despite this being a fairly common hope in the fandom. the open world was fine - nobody seemed to complain much about that, but it also didn't have much going on that inspired strong reactions out of people, either. you still saw the occasional snipe over a lack of co-op or a fixation on the game's lack of diverse ecological biomes, but overall, reception seemed almost muted and neutral within the community, as if complaints about multiplayer were taking oxygen away from any significant discourse about if the single-player content was really good or bad.

with the campaign being what it was - a single-player experience with only so much content to unpack - it drifted out of the broader fandom discourse fairly quickly. all eyes were on multiplayer, and 343 Industries began making a few lateral moves to try and address concerns at a lower level, through additions that wouldn't disrupt the flow of developing new content. new playlists were added into permanent rotation, experience was tweaked such that you could level up once per day through any level of participation in six matches, and store prices began skewing lower, although still perhaps walking the fine line of what i would call reasonable. many of those complaining about a lack of progression found themselves suddenly finished with their battle pass, and events proved to be fairly small in scope, generally introducing a new mode into rotation along with a temporary 'event pass' consisting of 10 free levels of cosmetics. again, the narrative around Halo Infinite mutated - "there's nothing to grind for, so why should i play Halo Infinite?"

PART FOUR: THE PROBLEM WITH LIVE SERVICE

as Season 1 continued, complaints around Halo Infinite steadied out, to some extent - less of an explosive reaction out of fans, but a general disdain over the pace at which features were arriving. from week-to-week, you could see the pendulum swing back and forth with the multiplayer's capstone rewards. if they were 'low effort', people would protest that they had 'no reason' to play the game for the week, but anything 'too good' saw complaints that 343 was keeping items away from players and deploying FOMO (fear of missing out) tactics. challenges themselves were also highly scrutinized, even when intentionally tuned towards easier tasks, such as completing 5 matches in a particular mode, or earning 10 kills with a basic starting weapon. the developers tried to stay on top of these complaints and emphasized that short-term changes were not the end of the process, but the tone amongst the community was getting unavoidably negative in terms of the overall impression of Halo Infinite.

one of the larger missteps in the first few months was a networking glitch that left Big Team Battle out of commission for a few weeks over the end of the year, which definitely didn't make matters any better, but once the holidays were over and the team could get back to full-time examination of the netcode, the matter was resolved. even beyond this major incident, the subject of netcode in Halo Infinite has been an infamously touchy one for the fandom, with many players bemoaning 'desync'. to this end, 343 Industries released an extensive report on how their online matchmaking works, and, to be quite frank about it, essentially had to explain the framework of how online multiplayer works for any given video game.

my opinion on this is undoubtedly biased - i have never experienced desync in Halo Infinite. i live in a region where it's not difficult to find matches with solid connections. i am sure that for someone who feels like they've experienced this hands-on, it's very frustrating, and i don't want to downplay anyone's experience being diminished by feeling that the game is performing unreliably. where i personally take issue with the debate around desync is in the hyperbole of it all - i don't think Halo Infinite has magnitudes more lag than any other modern online game, and i find that those who claim it makes the game 'unplayable' seem unwilling to examine the factors that create lag in video games.

the unfortunate truth of any online game is that, yeah, if you happen to live in Australia or whatever, solid connections are going to be harder to come across, and that's not necessarily Halo Infinite's fault - i just think people might notice it and feel stronger about it due to the game's competitive nature. the way 343 Industries explains the issue, to me, reads as though they're laying down pretty basic principles about how online games compensate for different levels of connectivity, principles that i thought most people kind of understood and made their peace with several years ago.

this felt like a fairly common cadence of interactions between fans and 343 Industries as Season 2's release at the start of May 2022 got closer and closer. players' frustrations would boil over - often headed by YouTubers who, by the nature of the algorithm that helps them ride the thin line of profitability, are incentivized to emphasize controversy and conflict - and 343 Industries would find themselves on the back foot, having to explain that, yes, video games have lag, yes, they're still working on those features you want, and yes, they hear all the feedback flooding in at them.

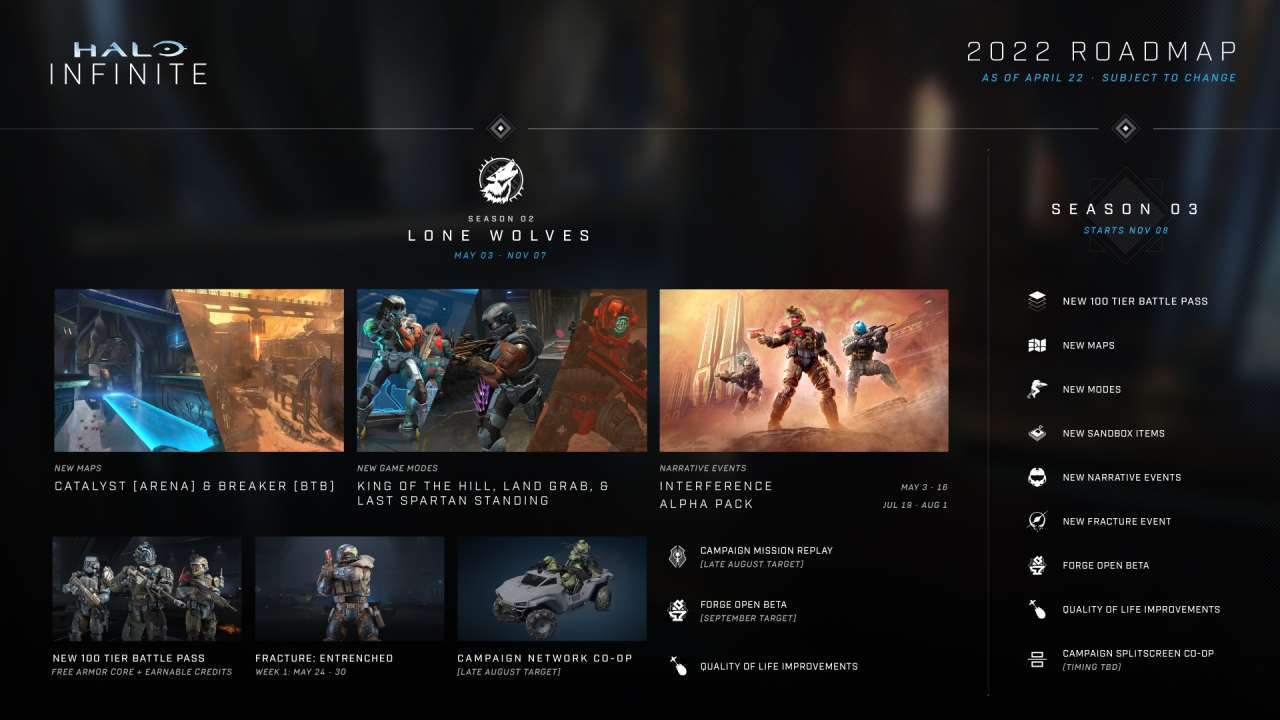

March 2022 represented the first major communication on what would be arriving in May with the release of the newly-titled Season 2: Lone Wolves. the blog post announced two new maps, new armor cores, and began laying out the 'theme' of Season 2, with new characters who would be involved in 'narrative events' for multiplayer. this blog post also came with the announcement of a delay for co-op, with the developers noting that creating co-operative play for an open world sandbox is vastly different from doing so for a linear title like previous Halos. the part of the blog post that still sticks with me the most, both personally and as a piece of the larger narrative around Halo Infinite and its fandom, is the introduction, where the team re-emphasizes their priorities when it comes to developing a live service game.

I'm here to answer two questions that we know are top of mind for the Halo community: "What is the Halo Infinite team working on right now?" and "When can we expect new content and features?" I'll start with brief answers, and then get into more detail, including sharing some new info on what's coming with Season 2.

This is the focus of the Halo Infinite team, in priority order:

1 - Addressing issues negatively impacting the player experience.

2 - Completing Season 2 and delivering it as promised on May 3rd.

3 - Continuing work on Campaign Co-Op, Forge, and Season 3.

We also have a "Priority Zero," that undergirds everything we do, namely: team health, with an emphasis on getting ourselves into a sustainable development rhythm so that we can deliver great experiences to all of you while keeping a healthy work/life balance.

Priority Zero means that we sometimes need to move slower so that we can move faster later. Frankly, these last few months have been slower than we expected, and we sincerely thank you for your patience as we stay true to the priorities, above.

- Joseph Staten, from 'HALO INFINITE UPDATE – MARCH 2022'

the community was constantly demanding stronger communication and transparency, and, at least in my opinion, that's what 343 Industries attempted to provide - an understanding that they recognize that things have been moving slowly, but that they're committed to team health above all other things and that sometimes, progress comes in the form of laying down foundations for more robust additions later.

i think now is a useful point in this rambling essay to take a bit of a reality check and recognize something - companies are not your friends. i'm not writing this with any intention to defend the broader corporate structures of 343 Industries or Microsoft. often times, when a company is telling you what you want to hear, it's too good to be true, and it's a very good impulse to look at anything like this with skepticism. where i diverge from that kind of thinking, in this case, is on two fronts.

the first front is that this communication does not come across as anyone trying to have their cake and eat it too. nobody at 343 Industries seems to be attempting to say that they could instantly tackle negative feedback and maintain a healthy work environment. there is an implicit sense that this is hard news to be broken to fans, but necessary news nonetheless about the realities of creating and maintaining a modern live service game.

the second front, then, is how fans of Halo took this bad news, which was incredibly poorly. many bemoaned that there were only two maps being released after a six-month wait, and even more criticized the decision to delay co-op, once again looping back around to that familiar refrain of "all these other games had this, so why can't Infinite?" and downplaying how changes in game design can make feature implementation harder. at times, you could clearly see a tendency to try and talk 'around' the team's priority for health, as if they could bargain their way towards an 'acceptable' amount of crunch to put the developers through to make the game better.

an important piece of the puzzle around team health in Halo is that the series is infamous for some of the hardest, most public crunch in the history of the video game industry. Halo 2 is notorious for coming in hot. with its 2004 release window rendered an immovable hurdle by the incoming launch of the Xbox 360 the following holiday season, the team at Bungie was forced to create the finished game in a little under a year - an outwardly impressive E3 demo had been a nightmare internally, and the game's graphical engine had to be essentially recreated from the ground up afterwards. Halo 2's iconic multiplayer, as relayed by designers years after the fact, was essentially a side project to what would have been a larger, more Battlefield-esque experience. this side project, nicknamed 'the party game', had to be immediately brought up to the front as development on the game's 'true' multiplayer stalled. Halo 2's story infamously ends on a massive cliffhanger because ultimately, the team had no time to finish their fight.

Bungie had to cancel multiple new games in order to get all hands on deck for Halo 2, and even then, developers were going so far as to live in their offices, sleeping under their desks and, in some extreme cases, irreparably damaging their marriages to finish this game. Joseph Staten himself would have been present first-hand for a lot of this, so i can only imagine that he, more than most, would understand the importance of creating a sustainable development environment. if you want to hear more for yourself, the details aren't some shameful secret - there's plenty of sources covering the process, including an excellent article from Waypoint (now fully absorbed into parent company Vice) called The Complete, Untold History of Halo which i cannot recommend enough.

historical lessons aside, the mounting frustrations in the community only continued as Season 2 got closer. at best, it seemed like fans were willing to selectively overlook 'priority zero', and at worst, you would see people argue that perhaps a little crunch is necessary for the sake of consumer satisfaction, or, as i said, trying to bargain around it, saying that they just needed to throw more people and more money at the problem to make it go away. even before the previously mentioned March 2022 update, a common refrain amongst fans were demands for a roadmap.

roadmaps have become a pervasive symbol of the modern 'game as a service', laying out long-term targets in an easily digestible forward-facing marketing graph. the reason Halo Infinite didn't have one at the time, as related by the developers, was a desire to ensure that any targets being provided could be relied upon, with goals achievable under the current framework of their development pipeline. it's not that Halo Infinite didn't have content coming, it was that the developers were savvy enough to know that unexpected problems come up all the time in the process of making games, and that any target would need to be solid, as delays would inevitably lead to an even more volatile community.

the April 2022 update would bring people the roadmap they had spent months demanding out of the studio, and it once again came as a tough pill for many to swallow, as Season 2 would end up lasting six months rather than the initially planned three-month cadence. many of the features that had been hot button issues amongst fans would still launch at roughly the same time that they would have on a three-month seasonal rotation - i.e. an open beta for Forge was still listed as due for September, which was always the plan, regardless of the strict seasonal label - but nonetheless, people went ballistic. on the campaign side, co-op was split down into two broad components, with online co-op targeted for August and local splitscreen listed as a feature for Season 3. many swore this kind of roadmap would 'kill' Halo Infinite, pointing heavily to the fact that the game would have only received two additional maps by the time it had crossed its one-year anniversary.

this roadmap also announced the next major form of communication fans would receive from the studio - a livestream on the following Wednesday going over Season 2 in greater depth, covering its battle pass, narrative framing device, and the three new modes coming to multiplayer. these types of streams had happened a few times now, namely around the game's multiplayer testing, in a dedicated recording space at 343 Industries - which, side note, never quite been sure what's up with this room. is that camouflage print or a bunch of fake leaves behind them? where does the wall end and the floor start? what's with that football helmet in the back?

anyways, i'm not going to recap this entire one-and-a-half hour livestream here, but there are a few key moments worth pointing out for how the fit into the ongoing discourse around Halo Infinite and how 343 Industries has attempted to respond to feedback. the first is a long segment in which community director Brian 'ske7ch' Jarrard sits down with Joseph Staten to talk about what the team's goals with Season 2 are, with discussion around how the team plans to implement more frequent mini-updates (nicknamed Drop Pods, after the ODST vehicles from Halo lore) to address quality-of-life concerns between major updates, or how certain features like a more traditional progression system are on the team's mind as long-term goals to work on. the most prominent and telling moment, however, was this -

Well, one thing to make really clear; none of us inside of 343 look at this roadmap and are happy with it. All of us want to be doing things faster, to deliver more content. You know, we still have this desire to get into a rhythm - a healthy rhythm - where we can ship a season every three months. So, for us internally, it was painful, frankly, to communicate this roadmap with a season that was gonna run for another six months.

- Joseph Staten, from 'Halo Infinite | Season 2 Community Livestream'

this conversation continues and goes over points like how the team tries to prioritize their short-term and long-term goals, but i think the quote above really sums something up - 343 Industries has been fairly candid about the fact that they know their game has shortcomings. and honestly, of course they do. those developers, probably more than anyone else, are hyper-aware of what people want out of Halo. it is their entire function as a studio to guide the franchise and they are receiving constant input from an incredibly vocal fanbase.

the other section that i would put focus on is around customization and what players can earn. challenges and store prices are being tweaked, the team is working to begin breaking down the walls of armor cores to allow for more mixing and matching, but the notable story to me is a shift in the battle pass - Season 2, unlike the first, would contain in-game currency on its paid track, allowing players to earn back the same amount the pass itself costs. they acknowledge within the stream that this is 'industry standard' for battle passes in other games, but also note that Halo Infinite didn't have that at launch because unlike those other games, its passes don't expire. other games are generally capable of eating these losses specifically because of that time limit, but Infinite doesn't have that.

so just to sum it up - on top of having lengthened seasons and an ever-increasing pace to progression as players continue to complain about challenges, Infinite has a permanently available pass that pays for itself. unless something in this set-up bends or breaks, the $10 that myself and thousands of other players put into the Season 2 battle pass is the last battle pass we'll ever have to spend real-world money on.

the livestream quelled a bit of rage from the fandom for a brief time, but it wouldn't be long before Season 2 released, and with the update in players' hands, it was sort of inevitable that people would latch onto new issues. in the days following Lone Wolves' launch, it was a bit of a death by a thousand cuts from different corners of the community - pro players were outraged that 343 would patch out unintended map geometry without consulting them first, campaign players were outraged that 343 would patch out an unintended superweapon, and casual players grew frustrated with the update's new Last Spartan Standing mode, primarily because with its elimination-based gameplay, it didn't always immediately register completed challenges.

it didn't matter if people enjoyed the new maps and modes that had been added, or that several improvements to progression had come to fruition, making Halo Infinite's battle pass both incredibly low-investment and relatively easy to clear in a matter of weeks. Season 2 was swiftly and loudly written off by the community as simply not being enough, and they made sure to let anyone with a passing interest in how Halo was doing know just how dead and unsalvagable the game was, which is definitely a good way to attract new people to your hobby.

as of this writing, we are in the last few weeks of Season 2, and while we'll continue to dig into how 343 Industries has communicated about their game and what's on the horizon, the actual status of the game on a day-to-day basis has been relatively steady. events have rolled in and out, store prices have remained lowered with only a few exceptions, and the game has received a handful of the promised 'Drop Pod' updates, bringing in features like better challenge visibility or the very early beginnings of tearing down the boundaries between armor cores. Last Spartan Standing is already gone, unless you happen to find a group of people playing privately - the stats were showing people didn't want to play it, yet despite this, the second its removal was floated as an option, you had people coming out of the woodwork to talk about how Last Spartan Standing was so good, and how 343 must be making some kind of huge mistake.

one of the more notable community developments was a test of online co-op play for campaign, offered through the Insider program. i didn't participate in this testing, but my understanding from the outside is that it went off without a hitch; some people have complained about 343's solution to open world co-op, where players are reined within a certain distance of each other, but the actual networking seems to have worked fine. the actual co-op, however, was ancillary to this test's impact on the community, because whether it was intentional or not, the Insider build also included a semi-functional build of the game's upcoming Forge map editor.

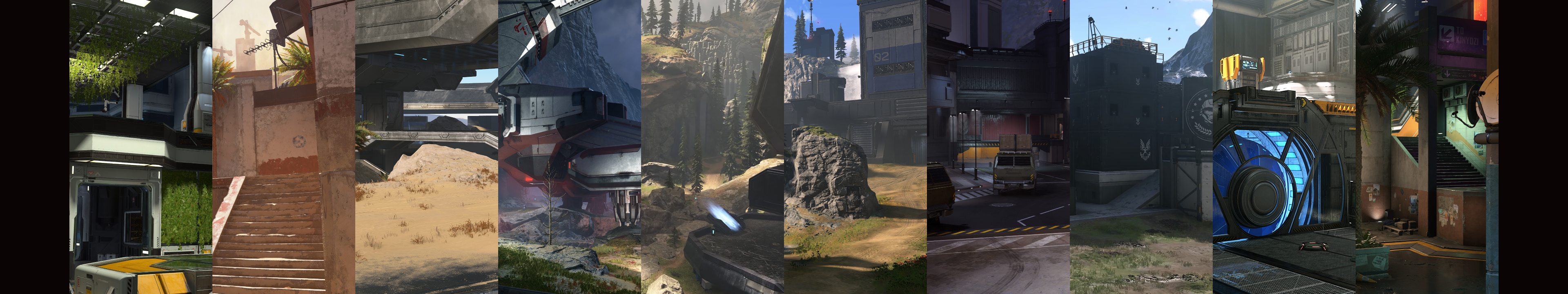

it has quirks and limitations - certain features like advanced lighting are unavailable, saving maps requires some intensive makeshift solutions, and the blank canvases meant to go with Forge aren't present - but other than that, the editor's in solid working order. once dedicated fans cracked the code of saving their maps, the community suddenly had a window into the game's future. only a select few people had the necessary builds and proper knowledge of how to utilize them, but those select few got to work immediately, showcasing all kinds of incredible maps. 343 saw all this, and seemed fine with it. why bother putting your foot down when this is building excitement in the community around what Forge can do?

the downside to all this, then, was people trying to fit the excitement of Forge into their pre-conceived notions that Halo was doomed to failure by the people who were making it. the narrative quickly became that Forge was going to be Halo Infinite's sole saving grace, with some going as far as to say that, since players made these maps, that only those players deserved any goodwill for 'fixing' the game, that 343 Industries was planning to leech off the good will of user-generated content. i certainly think there's a conversation to be had around the effort fans put into creative tools like Forge, and what the best practices are when it comes to the developers giving these passion projects a platform, but when people establish an outright hostile sense of ownership over Forge, using it to throw around claims that it's "pathetic" that fans make more maps than 343, something about that balance doesn't sit right with me.

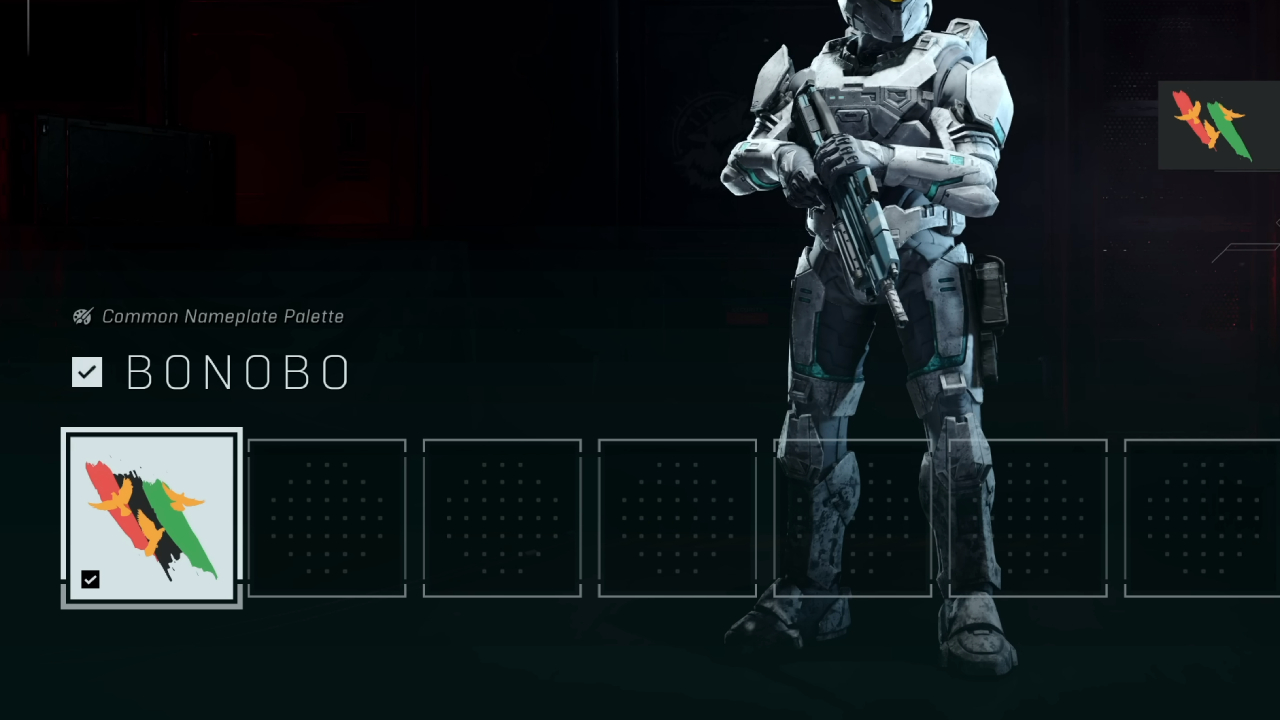

to close out this overview of Season 2, i want to rewind to a bit before that co-op test and talk about an actual grievance i do have with 343 Industries, one that is worth highlighting for a lot of reasons. it is fairly common for 343 to pay some basic lip service to real-world observances - things like Mental Health Awareness Month, or Women's History Month - by including some small trinket for players who log in, like an emblem or weapon charm. for Juneteenth, a day celebrating the emancipation of slaves in the United States, players received one of these free emblems. on the surface, it was just another surface-level gesture; not exactly above and beyond, just the routine acknowledgment that they would give any similarly scaled holiday. the issue, then, is that in Halo Infinite, the palettes assigned to emblems have names, and the Juneteenth emblem's only palette, in the colors of the Pan-African flag, was labelled 'Bonobo', as in, a species of endangered ape.

several people at the time said things like "i shouldn't have to explain why this is so bad", and i do agree, but i still will explain it anyways, just so it's down in writing here; comparing black people to apes is abhorrent and wrong, drawing on centuries of loaded racist iconography.

a fix came as swiftly as 343 Industries could roll one out, renaming the emblem's palette to 'Freedom'. Joseph Staten and Bonnie Ross both publicly apologized, while community manager John 'unyshek' Junyszek offered up a brief explanation, saying that the name refers to an internal toolset and that the palette had mistakenly pulled the name of the toolset in as placeholder text. that's about all the official communication we ever received on the incident, and it was hotly debated at the time whether or not the explanation being offered up was legitimate.